Authored By

Nat Markey, Andrew Carr, and Mark Abraham (DataHaven)

Date

October 10, 2025

Table of Contents

Dollars Leaving Communities: Mapping the Local Impacts

Report Methods and Limitations

Introduction

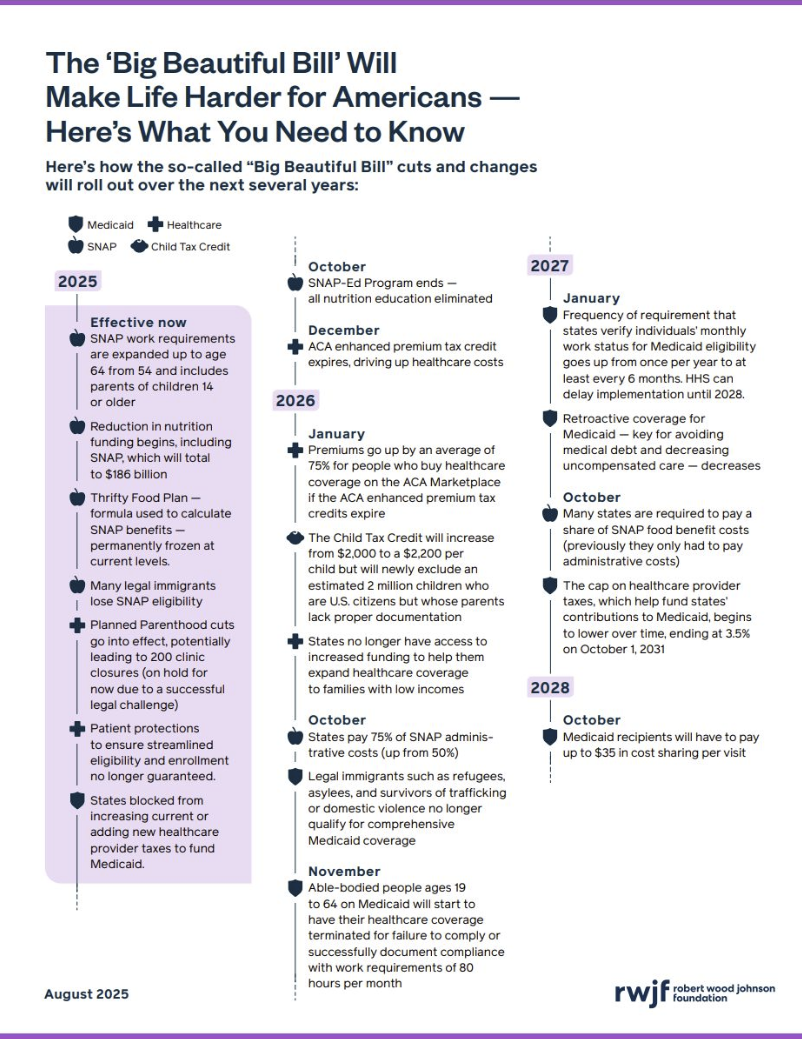

On July 4th, President Trump signed H.R.1, or the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act," into law. Over the next decade, the budget law will cut $186 billion of federal funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the nationwide food benefit system formerly known as food stamps. The legislation expands work requirements, limits cost adjustments, and shifts expenses to states. These policy changes are projected to cause tens of thousands of Connecticut residents to lose coverage entirely or see reduced benefits, even as the state pays more to keep the program running.

A July 2025 report from the Urban Institute estimated that 5.3 million American families, including 58,000 Connecticut families, will lose at least $25 per month in SNAP benefits due to policy changes in H.R.1. These 58,000 Connecticut families, making up about a quarter of all families in the state receiving SNAP, will lose an average of $194 in benefits each month. The Urban Institute report does not necessarily consider the law’s impact on state programs; for example, according to the Connecticut Department of Social Services (DSS), the effect on Connecticut's SNAP-LIHEAP "Heat and Eat" program may be particularly significant, causing decreases in SNAP benefits for tens of thousands of families in the state (discussed below).

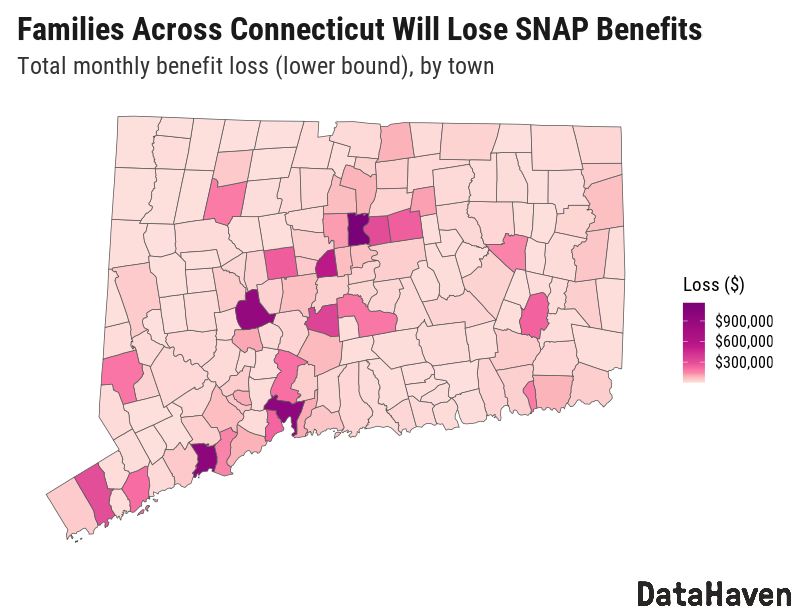

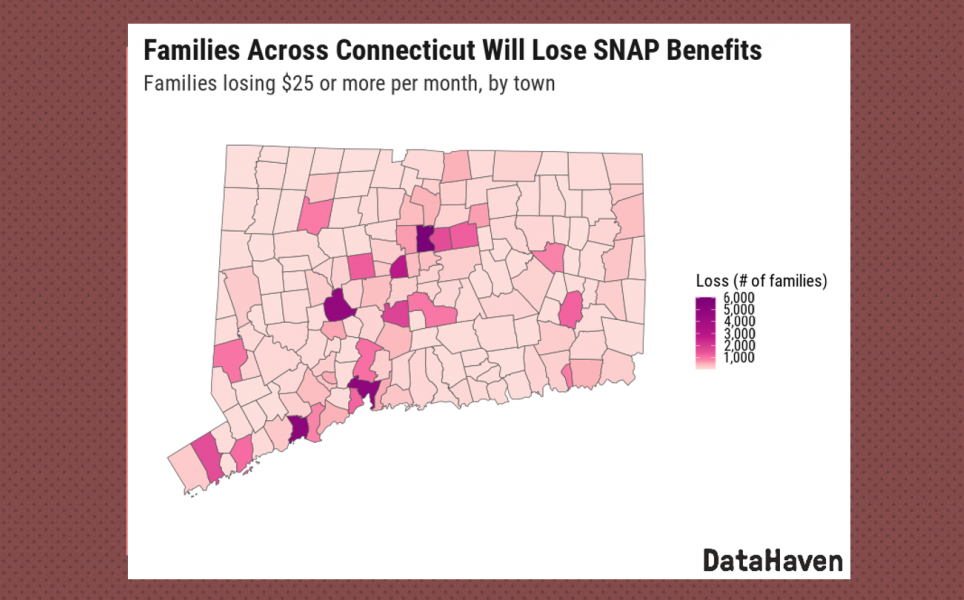

This DataHaven report estimates how many families in towns and legislative districts across the state are likely to experience SNAP benefit losses, and the cumulative local impact of those losses. In total, Connecticut SNAP recipients are projected to lose approximately $11 million to $15 million in benefits every month. Some of the state's largest cities will experience especially heavy impacts, with SNAP recipients in Hartford, Bridgeport, New Haven, and Waterbury each projected to lose approximately $1 million or more in monthly benefits. In the hardest-hit communities, including in these cities as well as within many suburban and rural parts of the state, total monthly benefit losses will represent a significant disinvestment from the local economy and a large reduction in neighborhood spending power.

Dollars Leaving Communities: Mapping the Local Impacts

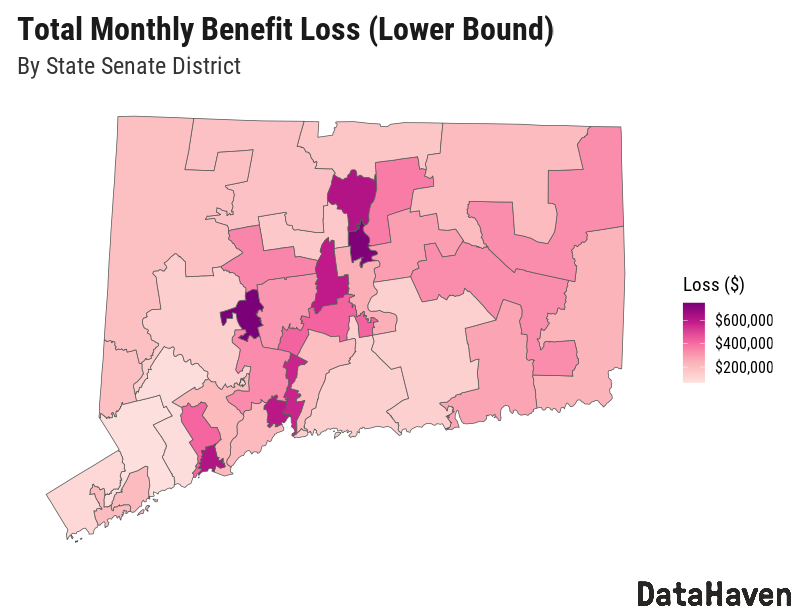

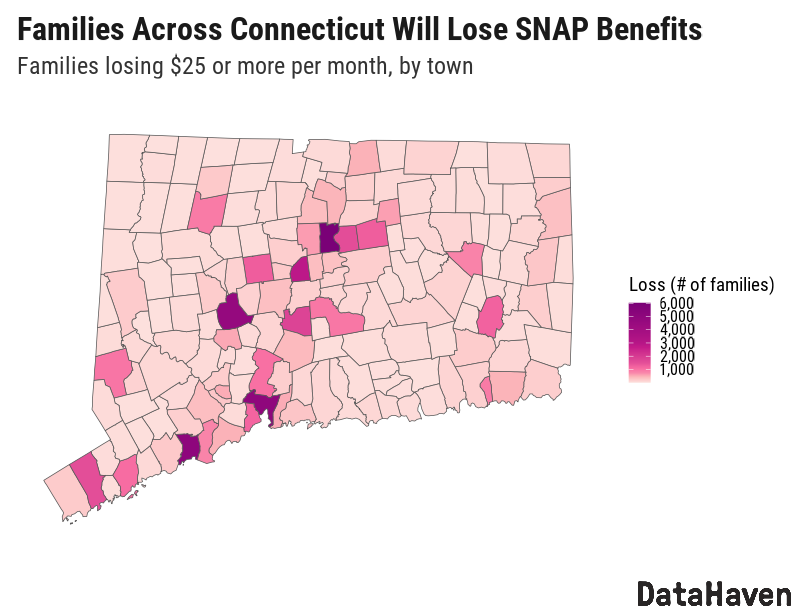

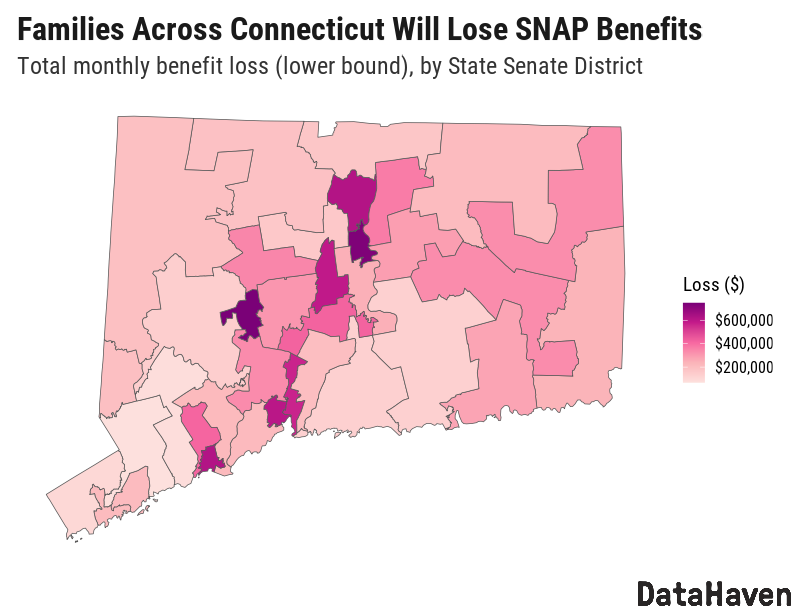

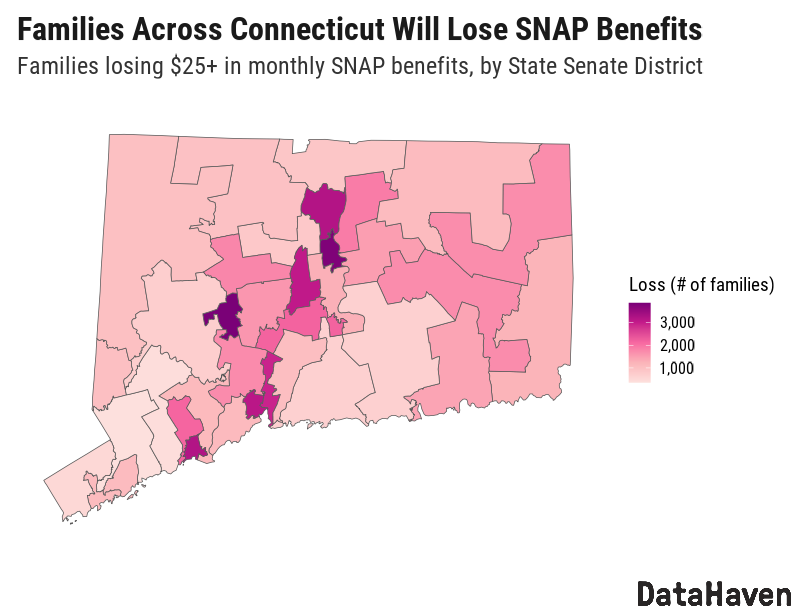

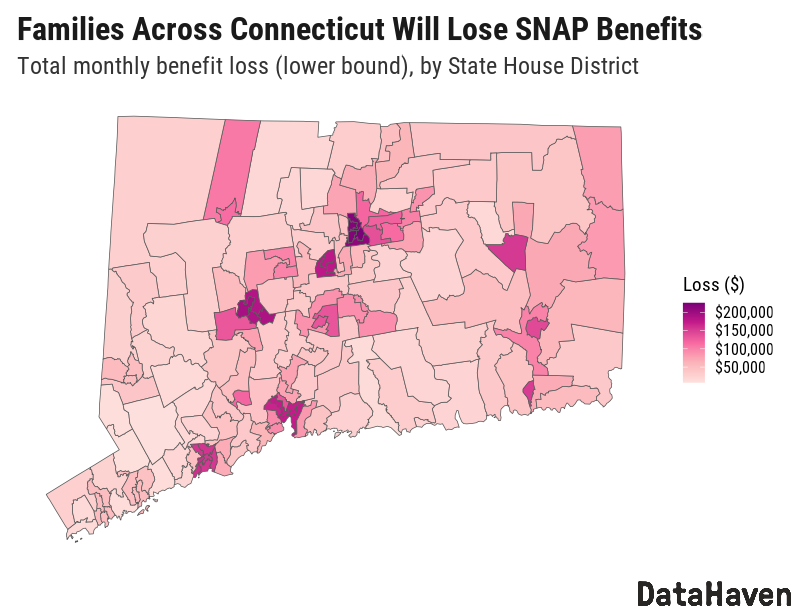

Using the numbers from the Urban Institute report as a baseline, DataHaven modeled the budget law's local impacts across Connecticut. Our maps illustrate the number of families projected to lose $25 or more per month in towns and legislative districts throughout the state.

DataHaven also estimated local impacts in terms of the overall dollar value of monthly SNAP benefit decreases. The maps below show lower bound estimates for the total monthly benefits lost across each town and legislative district. Our upper bound estimates (included in the interactive versions of the maps linked below) are about 35 percent higher across the board.

These local estimates do not take into account the indirect effects of SNAP, which include higher economic activity at local businesses, lower future healthcare costs due to improved nutrition (UConn Today), and other positive impacts. For example, recent research from the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University finds that every $1 cut in SNAP funding to families with children would result in $14 to $20 of long-run costs to society.

Among the 169 towns of Connecticut, these five cities are projected to see the largest number of families losing $25 or more in monthly benefits as well as the highest total funding losses:

- Hartford (population 119,970): 6,029 families losing $25 or more per month, totaling $1.2M to $1.6M in lost benefits per month

- Bridgeport (population 148,012): 5,045 families losing $25 or more; $970k to $1.3M per month

- New Haven (population 132,893): 4,955 families losing $25 or more; $960k to $1.3M per month

- Waterbury (population 114,356): 4,659 families losing $25 or more; $900k to $1.2M per month

- New Britain (population 73,301): 2,867 families losing $25 or more; $550k to $740k per month

In addition, some smaller municipalities will see similarly high benefit losses on a per capita basis, including Windham (23,905 residents; 794 families losing $25 or more per month, totaling $150k to $210k in lost benefits per month) and New London (27,199 residents; 895 families losing $25 or more; $170k to $230k per month), among others.

In each of nine Connecticut State Senate districts, at least 2,000 families are projected to lose $25 or more per month. Benefit losses will total at least $400k per month in each of these nine districts (from most to least affected, State Senate Districts 15, 1, 23, 2, 10, 6, 11, 13, and 22). In District 15 and District 1, benefit losses will be especially heavy, totaling between $700k and $1M per month. The nine most-affected districts are mostly urban, with six of them containing parts of either Hartford, Bridgeport, or New Haven. The other three draw the majority of their population from Waterbury (District 15), New Britain (District 6), and Meriden (District 13), respectively.

However, SNAP changes will have a major impact in more rural districts as well. For example, in State Senate District 29, which includes Mansfield, Windham, Killingly, Putnam, Brooklyn, Canterbury, Pomfret, Scotland, and part of Thompson, 1,710 families will lose $25 or more per month, a loss of $330k to $440k per month for that area.

The five State House Districts with the highest projected losses (Districts 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7) are all primarily within Hartford, highlighting the state capital’s vulnerability to SNAP cuts. Families within each of these five districts are projected to lose approximately $200k to $300k in SNAP benefits every month, with more than 1,000 families in each of these districts losing at least $25 per month. State House Districts in many smaller communities, such as areas of Torrington, Ansonia, Norwich, Meriden, New Britain, Bristol, and Northeastern Connecticut, will also be heavily impacted.

At the state level, certain demographic groups are likely to bear a disproportionate impact from SNAP cuts, based on household SNAP enrollment statistics from the 2023 five-year U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey. Households below the poverty line make up 11% of Connecticut’s population, but 41% of SNAP recipients in the state. Married family households receive SNAP at a rate of 5 percent, compared to 28.5 percent for single-parent and other unmarried family households.

In Connecticut, the greatest number of households receiving SNAP have a householder who identifies as Non-Hispanic White (63,550 out of 974,286 Non-Hispanic White households, or 6.5 percent, receiving SNAP). However, other racial/ethnic communities, including Latino (57,830 out of 203,457 households, or 28.4 percent), Black (36,404 out of 145,077 households, or 25.1 percent), and Asian (4,553 out of 58,069 households, or 7.8 percent) have higher proportions of households receiving SNAP.

Interactive Maps and Data

In addition to the static maps published above, DataHaven created interactive maps showing town and district-level SNAP impacts of H.R.1 in Connecticut. These maps, as well as a spreadsheet with the underlying data, are publicly available below.

- Families projected to lose $25+ per month and total monthly benefit loss, by town

- Families projected to lose $25+ per month and total monthly benefit loss, by State House District

- Families projected to lose $25+ per month and total monthly benefit loss, by State Senate District

Discussion

Understanding SNAP Coverage Losses

One of the most impactful SNAP changes in H.R.1 is the expansion of work requirements, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects will amount to $68 billion in budget cuts over the next decade. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that at least 21,000 adults in Connecticut are at risk of losing SNAP eligibility due to expanded work requirements in the law. Specifically, parents with children ages 14-17, older adults ages 55-64, veterans, young adults 18-25 emerging from the foster care system, and homeless people will no longer be exempt from SNAP work requirements.

Those subject to work requirements can only receive benefits for three months out of every three years, unless they prove that they work at least 80 hours per month. When individuals lose coverage due to work requirements, it decreases the level of benefits received by the entire household, even though other people in the household may retain benefits. According to a report from the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, if the parent of a 14-year-old child lost SNAP eligibility, the entire family’s benefits would drop from $536 to $292 each month. Per the Connecticut Department of Social Services (DSS), implementation of the new work requirements will begin on November 2, 2025.

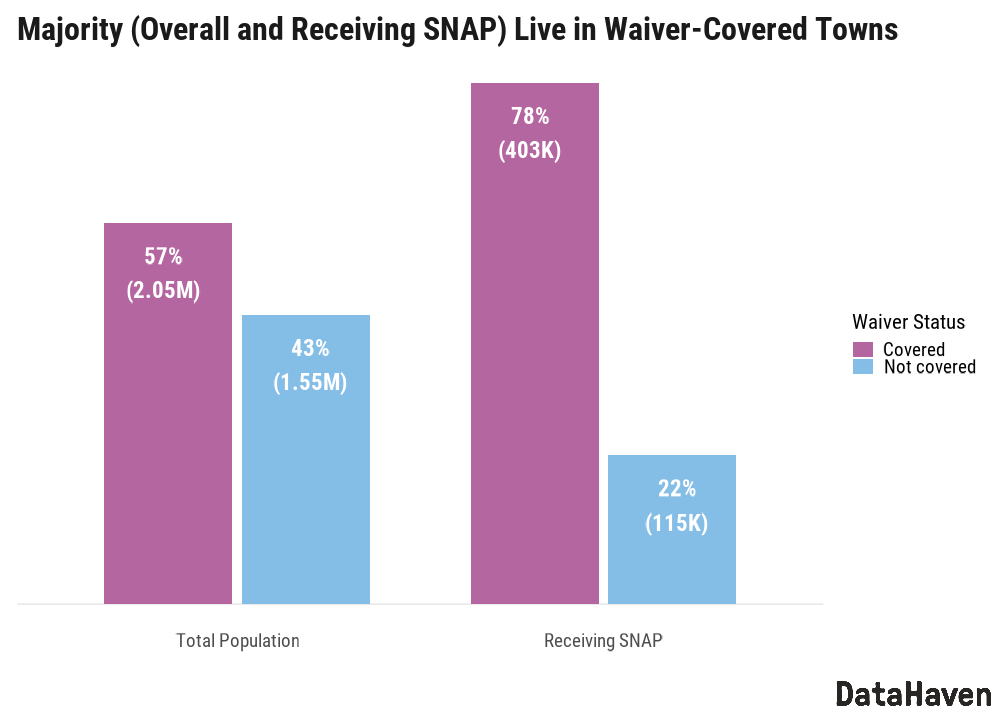

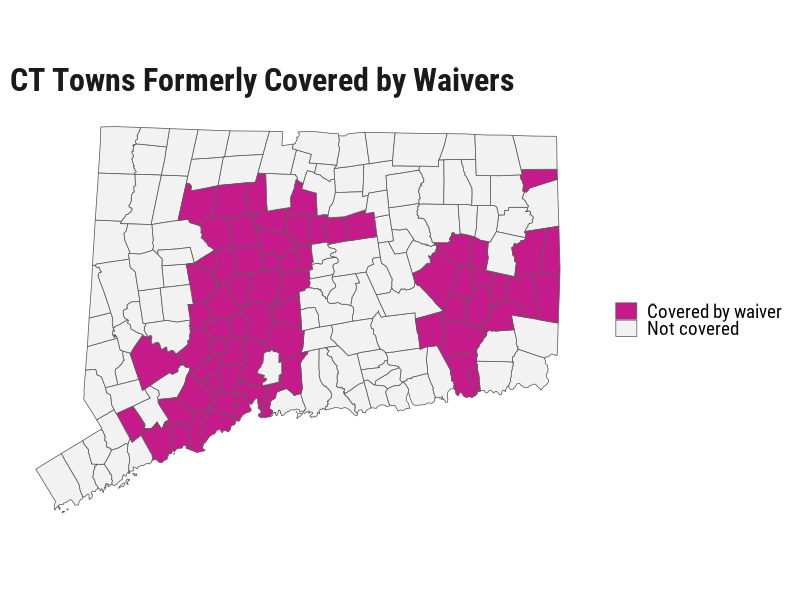

Additionally, nearly half of Connecticut towns will lose location-based work requirement waivers, as the process to receive a waiver for high local unemployment becomes stricter. Sixty-eight towns in Connecticut, which contain the majority of the state’s population and over three quarters of the state’s SNAP-recipient families (see map below), currently have work requirement waivers for high unemployment. Under the new standard of 10% local unemployment, however, zero towns in Connecticut qualify for waivers. In an informational session before the State Senate Appropriations Committee on October 16, the Connecticut DSS projected that approximately 20,000 people currently covered by town exemptions are at risk of losing SNAP eligibility under new work requirements, with coverage expiring as early as November 30 for 1,500 of these individuals.

Ultimately, the exemption cuts will increase the number of low-income individuals across Connecticut and the nation subject to work requirements in order to receive SNAP. Research has shown that SNAP work requirements are ineffective in encouraging employment, hurt the neediest benefit recipients most, and cause working people to lose benefits purely due to the administrative burden of proving employment status (Yale Tobin Center, The Hamilton Project, Harvard SPH). Brantley et al. (2020) also identify significant racial and ethnic disparities in the impact of SNAP work requirements.

In addition to losses caused by expanded work requirements, Connecticut residents will lose coverage due to the elimination of eligibility for noncitizen lawful immigrant groups, including refugees and asylees. Nationally, the CBO predicts that these changes will cause about 90,000 people to lose SNAP benefits in an average month.

Understanding Decreases in SNAP Benefit Levels

Although many Connecticut residents will lose SNAP benefits entirely, those who retain coverage are still likely to receive lower benefit levels. Benefits will drop in part due to limitations on future cost-of-living adjustments to the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), a standard maintained by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for the cost of a nutritious, budget-conscious diet. The TFP serves as the basis for the maximum level of SNAP benefits. The USDA will continue to adjust the TFP for inflation based on the consumer price index monthly, but H.R.1 limits more systematic increases. In particular, the TFP may not be reevaluated before October 2027, and all future changes must be cost-neutral (USDA). The cost neutrality requirement means that, regardless of any changes to dietary patterns and nutritional guidelines, USDA will not be able to increase SNAP benefit levels, aside from standard inflation-adjustment. The Thrifty Food Plan provisions of H.R.1 will decrease SNAP spending by $37 billion in the next ten years, according to the CBO.

This restriction on Thrifty Food Plan adjustments comes despite evidence that current benefits are inadequate to afford a nutritious diet, especially given fast-rising food prices over the last few years. As of late 2024, the cost of a modestly-priced meal exceeds the current maximum SNAP benefit level in 99 percent of U.S. counties, including all of Connecticut, according to research from the Urban Institute. The cost disparity was particularly high in the Western Connecticut Planning Region, where an average modestly-priced meal cost $4.30, which is 52 percent greater than the maximum SNAP benefit per meal of $2.83. The most recent overhaul of the Thrifty Food Plan, in 2021, was temporarily effective in addressing such gaps: it increased SNAP benefits by 21 percent, keeping an estimated 2.9 million people out of poverty (Urban Institute). Immediately after the 2021 changes, the share of counties where the cost of a modestly-priced meal exceeded the SNAP benefit level dropped from 96 percent to 21 percent, but that percentage quickly shot back up due to increases in food prices beyond inflation. Under the new legislation, such changes to address the adequacy of SNAP benefit levels will no longer be possible.

H.R.1 also limits the so-called “Heat and Eat” program to households with an elderly or disabled member, further decreasing SNAP benefit levels for some Connecticut residents. “Heat and Eat” links SNAP benefits to the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). Under the SNAP-LIHEAP connection, households that qualify for LIHEAP assistance on utility bills are able to claim higher deductions for energy costs from their income, increasing the level of SNAP benefits they receive (FRAC).

With new restrictions on the program, SNAP and LIHEAP recipients who no longer qualify to link the two will see lower SNAP benefits. In its October 16th presentation to the Appropriations Committee, the DSS shared estimates that 50,000 Connecticut households would lose Heat and Eat eligibility, with each household losing $100 of SNAP benefits per month. This change amounts to an additional $5M in lost SNAP benefits statewide each month. The DSS anticipated that Heat and Eat provisions would take effect in November 2025, as with the eligibility changes discussed above. Meanwhile, LIHEAP also faces its own headwinds, as the White House has proposed eliminating grants for the program entirely. The DSS estimates that over 100,000 households will need heating assistance this winter, a 12 percent increase from last year (CT Mirror). Families could feel a simultaneous pinch in both food and heating benefits.

Higher Costs for Connecticut

Even with coverage losses and decreased benefit levels for recipients, Connecticut’s state government will bear higher costs for SNAP, as H.R.1 shifts some of the program’s cost burden onto states. Starting in fiscal year 2027, Connecticut’s share of SNAP administrative costs will increase from 50 percent to 75 percent (UConn Today). Connecticut will be responsible for screening SNAP recipients to ensure they meet the new eligibility requirements, possibly further adding to administrative program costs.

Starting in fiscal year 2028, Connecticut will also have to pay between 5 percent and 15 percent of SNAP benefit costs, with the exact share depending on the state’s payment error rate (Urban Institute). This is the first time that states will be required to pay a share of SNAP benefit costs. Payment error rates can be quite volatile year-to-year, making it difficult for states to anticipate budgetary impact, and some states will face difficult decisions between paying more and cutting SNAP benefits (Center for Budget and Policy Priorities). In September, DSS Deputy Commissioner Peter Hadler estimated that SNAP changes would cost the state of Connecticut an additional $40 million to $120 million annually (New Haven Register). In the short term, Connecticut may also incur unexpected costs to keep SNAP running if the federal government shutdown persists (CT Mirror).

Additional Impacts

One change that has already taken effect is the expiration on October 1st of federal funds for SNAP-Ed programs. Connecticut was previously slated to receive $4.6M in 2025 for these programs, which aim to educate low-income families on nutrition. Organizations administering SNAP-Ed in the state will likely face cutbacks and job losses as a result of the funding cuts (WSHU).

Additionally, children in Connecticut could lose eligibility for free school meals and summer food benefits as their families lose SNAP. Children whose households participate in SNAP are automatically eligible for free meals, but the new SNAP cuts mean that some kids will lose this “direct certification” for benefits. Meanwhile, families and schools will face additional paperwork and administrative barriers to confirm eligibility for free meals (Center for Science in the Public Interest). In an average month, 96,000 children across the country could experience cuts to free meals and summer EBT because of losing automatic eligibility from SNAP (Center for Budget and Policy Priorities).

Conclusion

This DataHaven report creates local estimates that illustrate the impact of federal policies on communities across Connecticut. In addition to producing this report, DataHaven included new questions related to SNAP experiences and concerns about loss of benefits within its 2025 DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey. Results from that survey will be released later this year. We hope that residents and policymakers will use this information to help understand the impact that recent legislation will have on the place where they live and to advocate for improved well-being for all residents.

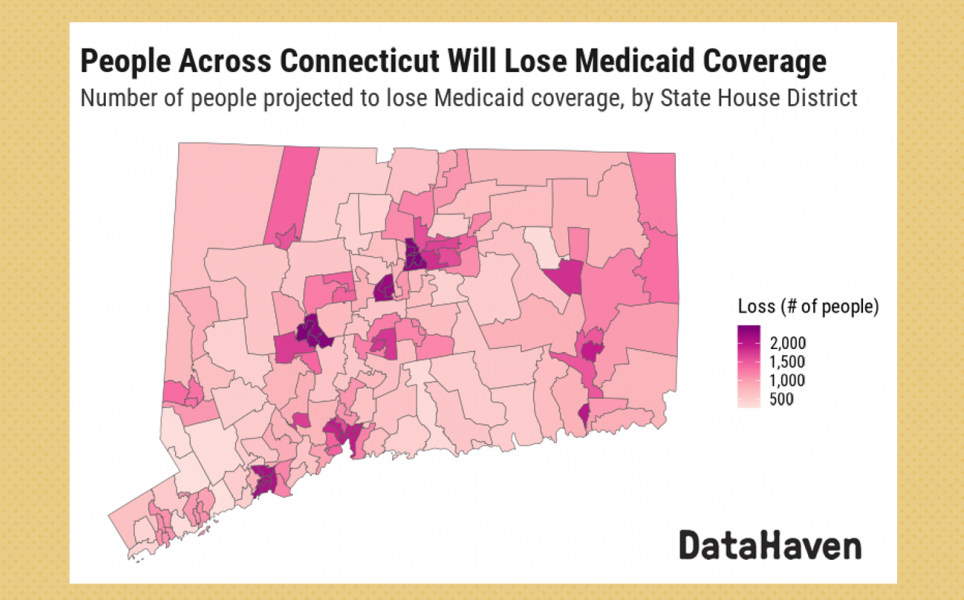

A recent DataHaven report entitled "Coverage at Risk: Projected Losses in Medicaid and Access Health CT by Town and Community," used similar methods to illustrate the local impacts of projected Medicaid/HUSKY and Access Health CT coverage losses, and was widely used by non-profits and policymakers to understand these changes.

These policy changes will create compounding burdens on communities; for example, in the City of Hartford, in addition to the over 6,000 families projected in this report to lose significant SNAP benefits, the "Coverage at Risk" report shows that 14,000 city residents are projected to lose their health insurance coverage. To help illustrate this timeline, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation released an infographic, which is included below.

Report Methods and Limitations

Methods. This DataHaven analysis is largely based on estimates from an Urban Institute report on state-level impacts of H.R.1 SNAP provisions. Specifically, Urban Institute researchers used their Analysis of Transfers, Taxes, and Income Security (ATTIS) microsimulation model to project the number of families losing $25 or more per month in Connecticut and the average monthly benefit loss for these families. The Urban Institute report uses the term “families” to refer to SNAP Assistance Units, which may include one or more people. DataHaven uses the same term throughout this report. See the Urban Institute report for more methodological considerations.

To obtain town-level estimates of the number of families losing $25+/month, DataHaven weighted the statewide total losses by each town’s share of SNAP assistance units as of August 31, 2025. The Connecticut Department of Social Services provided data on SNAP assistance units by town in response to an email request on October 1, 2025. DataHaven used town-to-district population crosswalks to produce estimates of coverage loss by State House and State Senate District.

At the town, district, and state levels, DataHaven obtained a lower bound for total monthly benefit loss by multiplying the number of families/households/assistance units expected to lose at least $25/month of SNAP benefits by the Urban Institute’s estimate of average monthly benefit loss for these families in Connecticut, which is $194 per month. An upper bound was then obtained by assuming that all remaining SNAP-recipient households lost the maximum of $25/month.

We would like to thank Meg Hadley Zimmerman of End Hunger CT!, the staff of the Commission on Women, Children, Seniors, Equity, and Opportunity, and the staff of The Connecticut Project for their help reviewing the final draft of this report.

Limitations. Our analysis assumes that the proportion of SNAP recipients losing benefits will be consistent across towns and districts. However, there are geographical variations in the age, employment, and other relevant characteristics of SNAP recipients that may impact the actual number of households who are likely to lose benefits. Detailed town-level, address-level, or other personal-level information that could allow DataHaven to produce more precise estimates of coverage loss for each community are not available at this time, and in many cases would be unlikely to be available due to concerns about confidentiality.

The Urban Institute’s ATTIS modeling, which provides the basis for this report, does not consider every change to SNAP in H.R.1. The Urban Institute analysis incorporates Thrifty Food Plan changes, state matching funds requirements, loss of eligibility for noncitizens, and the most impactful changes to work requirement exemptions. Urban Institute modeling does not capture elimination of work requirement exemptions for people experiencing homelessness and people under the age of 25 who were in the foster care system at age 18, nor does it capture the law’s extension of work requirement exemptions to American Indian groups. Therefore, this report also does not capture any decrease or increase in SNAP coverage due to these changes.

Most importantly, future changes in state and federal policy could reduce, or increase, the number of people who will ultimately lose SNAP benefits as a result of H.R.1. It remains unclear the extent to which states such as Connecticut will be able to respond to fill gaps in federal support for programs such as SNAP.