New Census Data Product Maps 40,000 New Connecticut Homes Since 2020: Not Enough to End the Housing Crisis

By Andrew Carr, Nat Markey, and Mark Abraham, DataHaven

Introduction

Connecticut is facing a historic housing affordability crisis. The state currently ranks dead last nationally in the number of active housing listings for every ten thousand households (see chart below), as well as in its ratio of housing units to households. Connecticut also ranked second to last in its rental vacancy rate, as of 2024. And according to the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness, homelessness in Connecticut rose by 44 percent since 2021, and unsheltered homelessness rose by 45 percent just within the past year.

For legislators and advocates working to address this crisis, having reliable data to understand the true scope of housing production is essential to crafting effective policy.

New U.S. Census data product could present a more accurate picture of housing production

Until recently, policymakers have relied on The Census Building Permits Survey (BPS) as a primary source to track new housing construction. However, these data have many limitations. For example, municipalities could underreport permits, and some projects such as conversions of non-residential buildings into housing are typically not counted. More importantly, building permits are a flawed proxy of the number of housing units. Permit data do not account for demolished buildings or buildings that have become uninhabitable. Sometimes, permits that are counted in the data do not result in completed housing projects.

The U.S. Census Bureau recently introduced a new data product, Census Address Counts, that could offer a better measure of the housing supply. More analysis is needed to determine if there are inaccuracies in this new dataset, but it could offer advantages over the building permit survey data. Census Address Counts uses Decennial Census and USPS data to provide the numbers of housing units at the block level, accounting both for new units as well as demolitions. Unlike the building permit data, these address counts are based on housing that has already been built. Data are available for 2020, 2023, and 2025.

For this report, DataHaven analyzed the new Census Address Count data to determine whether Connecticut’s housing supply is growing at a fast enough rate to address the housing shortage.

Geography of the new housing supply in Connecticut

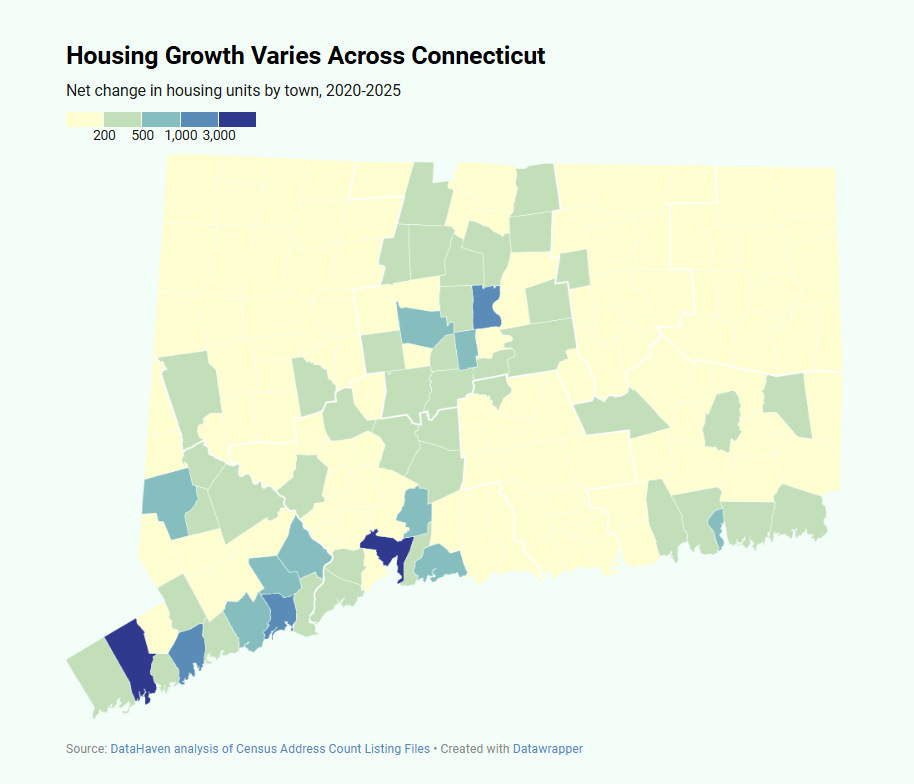

To understand where new housing is being added in Connecticut, DataHaven aggregated the Census Address Count data from the block level to the Regional Council of Government (COG), tract, and town levels. Census Address Count data by town is shown in the interactive map below. Click or hover over a town to see the net and percent change in the number of housing units, the number of units in 2020, and the number of units in 2025.

Over the past five years, the housing supply has increased unevenly across the state. Cities in the central and western part of Connecticut saw the largest increases in the numbers of housing units since 2020. New Haven added 3,535 units, Stamford added 3,512 units, and Hartford added 2,082 units.

Of the forty thousand units that were built since 2020, twenty-six thousand (65 percent) were in the Capitol, Western, and South Central COGs. These three regions are also home to 67 percent of Connecticut’s jobs as of Q4 2024, according to a DataHaven analysis of Quarterly Workforce Employment Counts. Overall, these areas also saw slightly more housing growth as a percentage of the number of housing units in these areas. The Western, and South Central, and Capitol COGs experienced a 2.8 percent increase in the number of housing units between 2020 and 2025, while the Northeastern and Northwest Hills COGs saw a 2 percent increase during this time.

The bar chart below shows a ranking of units added by town. Housing growth over the past five years has been heavily concentrated in a small number of towns. The ten towns with the most growth accounted for 39 percent of new housing in Connecticut. Stamford and New Haven added more homes than the bottom 100 towns combined.

Looking more closely at the neighborhoods within towns, it is clear that the most rapid increase in housing supply is generally taking place in downtown core areas, especially New Haven and Stamford, with comparably few new homes being added in nearby areas such as Milford and Greenwich that in some ways are equally if not more accessible to jobs and mass transit.

The map below allows policymakers to visualize the census tracts that have expanded housing supply by 12 percent or more, as well as those that have added very few new homes. You may need to use the buttons to zoom into small geographic areas such as downtown Stamford.

New data show progress, but not nearly enough to meet growing needs

Since 2020, the number of housing units in Connecticut has increased by forty thousand from 1,530,000 to 1,570,000. While Connecticut added 6,000 new units per year between 2020 and 2023, it added 10,000 new units per year from 2023 to 2025. This means that the rate of new housing supply in Connecticut also accelerated during this period.

Whether Connecticut can maintain this pace of new housing supply is unclear. It is important to note that despite the apparent increase in the rate of housing supply in Connecticut over the past three years, overall rates of new home construction in Connecticut each year have been among the lowest in the United States since the 2008 financial crisis. From 1998 to 2007, Connecticut permitted between about 8,000 and 12,000 new homes almost every year, but the number of permits fell sharply in 2008 and ranged from about 3,000 to 6,000 each year from 2008 through 2021. Looking forward, economic conditions, tariffs or other policies that increase the cost of materials, and immigration policies that reduce the availability of construction workers, call into question whether the current rate of housing production in Connecticut can be sustained.

According to the 2025 Connecticut Fair Share Housing Study, low-income residents in Connecticut face a shortfall of about 120,000 housing units. In other words, there are 120,000 more low-income households than there are housing units affordable to these households. The overall housing gap is even larger according to that report: up to 380,000 units statewide. At the current pace of new supply, it could take 50 years to close that gap. Even if the true shortage is smaller, producing enough housing would still take decades at today’s rate.

Demographic trends suggest that demand for housing will continue to rise. The number of households is growing. According to the Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, in 2024, there were roughly 78,000 more households than there were in 2019, an increase of nearly 6 percent. As residents live longer and more people retire, most “age in place” rather than downsizing or leaving the state. At the same time, demand is coming not only from workers moving into Connecticut to fill those existing job openings, but also from people already here: young adults leaving their parents’ homes or entering the workforce and forming their own households. Each of those transitions creates the need for additional housing. Average household sizes are also shrinking, as fewer people choose to live with roommates or extended family. As a result, even if the population were to remain steady, the demand for new housing supply would still increase with the rising number of households and the gradual loss of existing housing units (due to deterioration, fire, conversion to other uses, and other factors).

Rising income and wealth inequality is also driving up housing demand in counterproductive ways. Higher-income households are more likely to purchase large homes on larger lots, which could reduce the number of units produced on any given parcel of land. Wealthier households may even combine multiple units, for example, by converting existing two-family homes into single-family homes, by combining two apartments into one, or by tearing down two homes in order to build one larger home. Rising inequality could mean that the existing housing stock serves fewer households, exacerbating the shortage for everyone else.

Conclusion: A plan to address statewide housing insecurity

In summary, it could take several decades for Connecticut to build enough homes to meet current residents’ housing needs, at least at the current rate at which homes are being built. The newly-released Census Address Count data product featured here has block-level data that could help policymakers understand where homes have been built, and where they haven’t, perhaps more accurately than before.

Policymakers should consider legislation that could help accelerate the rate of new housing production, particularly in towns that are located near job centers such as Hartford, New Haven, and New York City. The recently passed H.B. 8002 has some zoning reforms, including prohibiting towns from requiring off-street parking of buildings with more than 16 units. However, the law leaves Connecticut’s zoning laws largely intact.

To create a significant increase in the rate of new housing development, policymakers could reform CT General Statute 8-2, which grants municipalities the authority to implement zoning restrictions and otherwise regulate land use. Other changes, such as allowing multi-family housing by-right in areas near transit and job centers, streamlining permitting processes and regulations (such as through “single stair” reform) to reduce the cost of construction, subsidizing the cost of infrastructure and brownfield remediation, converting underutilized state and municipal-owned properties into sites for housing development, and removing other barriers to construction, could also accelerate housing production. The Connecticut Business & Industry Association (CBIA) Foundation for Economic Growth & Opportunity has suggested approaches like these in its report on the economic impact of Connecticut’s housing shortage.

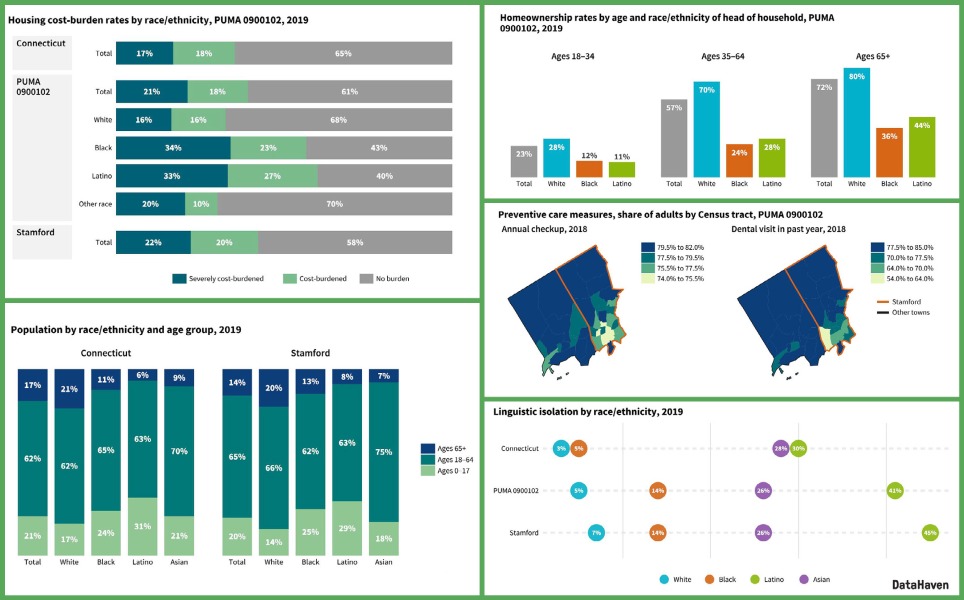

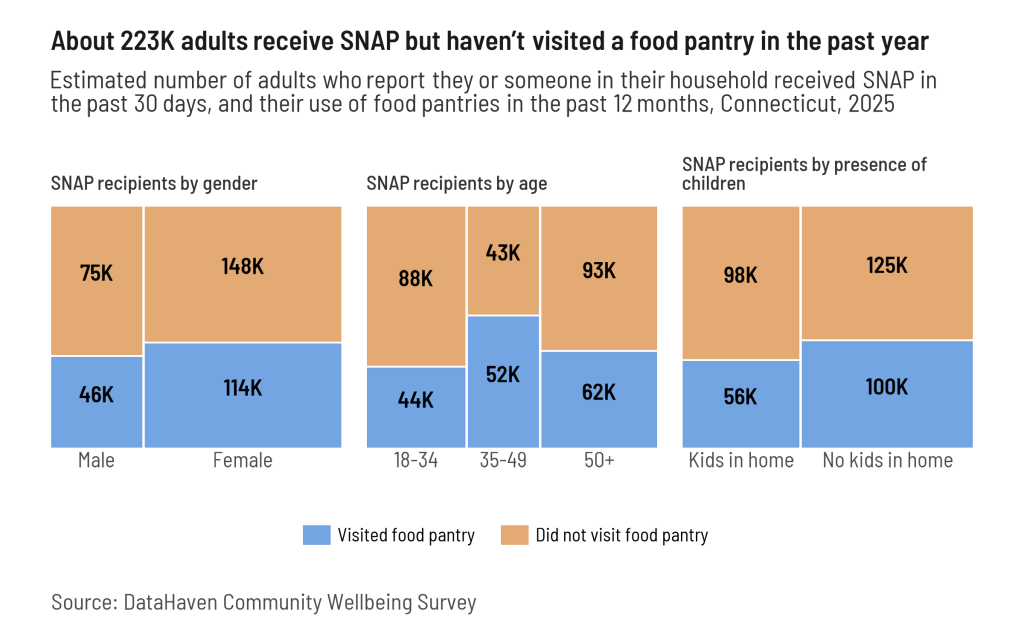

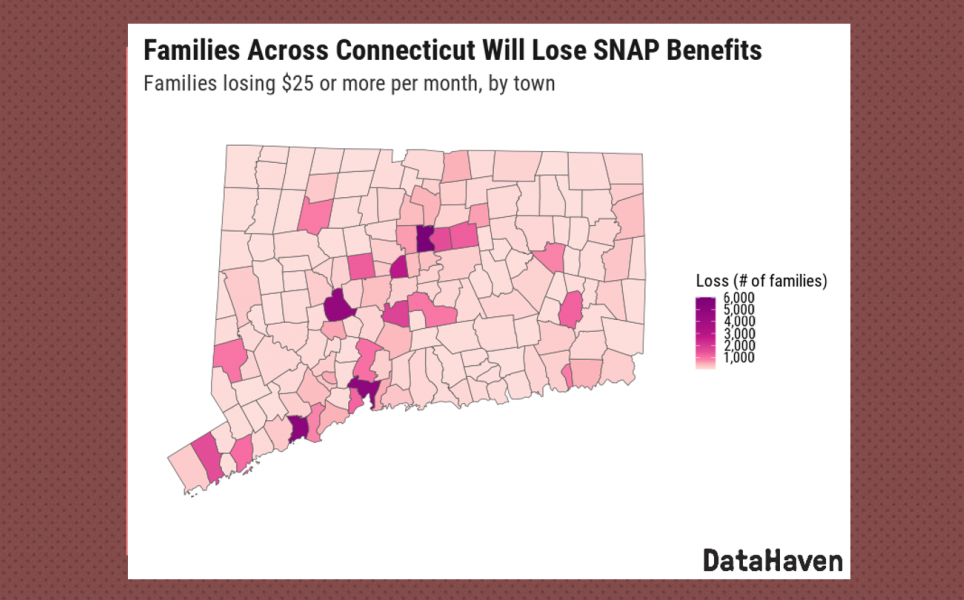

Given the rapid increase in homelessness and housing insecurity in Connecticut in recent years, immediate investments in housing subsidies, household-level tax credits, and supportive housing are essential to consider as well. According to the DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey, the number of adults in Connecticut who ran out of money to pay for their housing in the past year has doubled: from about 150,000 in 2015 to 300,000 in 2025. The survey also shows that this increase is associated with a large rise in food insecurity, especially among children, and rising numbers of adults postponing needed healthcare. The Connecticut Town Equity Reports show that housing affordability is an issue across urban, suburban, and rural towns throughout the state.

While this surge in housing insecurity, particularly among middle-income households, is largely driven by the state’s extreme shortage of housing, it cannot be solved only by new supply. Even with more homes and more stable prices, significant investments would still be needed to support vulnerable populations who face ongoing barriers to housing, such as lack of income, disabilities, health challenges, or family instability.

Connecticut is building new homes, and the pace of new supply seems to be increasing. But without significant reform, the state could be waiting a half century or longer to meet current housing needs. Bold action is essential to ensuring that all Connecticut residents have access to affordable, high-quality homes, to give employers the workforce they need, and to allow the economy to work in ways that benefit everyone.

Related Reports

Related Data

Dataset, Document

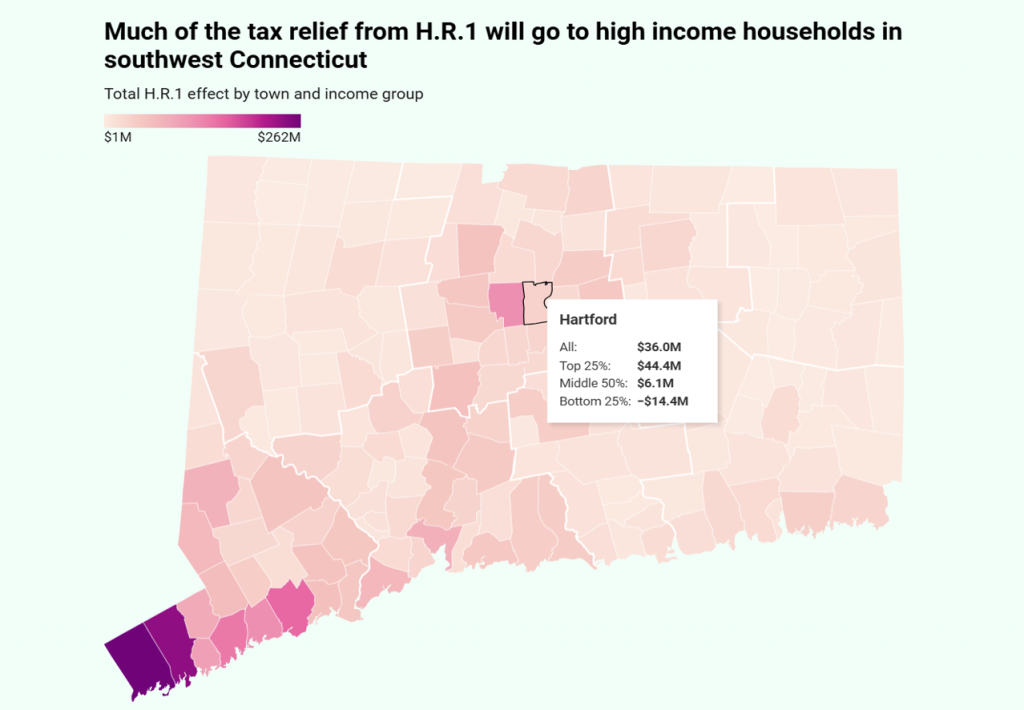

DataHaven HR1 Tax Effects Spreadsheet by Connecticut Town

Document

Wilton Town Equity Report 2025

Document

Winchester Town Equity Report 2025

Document

Windham Town Equity Report 2025

Document

Windsor Town Equity Report 2025

Document