All DataHaven Programs, Community Wellbeing Survey, Economy

07.20.2016

Dependence on smartphones may challenge Connecticut job seekers

—wordpress

Note: This article, by DataHaven intern Emma Zehner, originally appeared in the New Haven Register. You may view it there at http://www.nhregister.com/technology/20160720/dependence-on-smartphones-….

By Emma Zehner

Wednesday, July 20, 2016

An anonymous reader recently wrote into the New York Times Workologist column complaining that they had not heard back from any companies after applying for several openings a day on online job boards. Certain they were overqualified for the positions, the reader asked whether the term “resume optimization” might have anything to do with it.

In his response, columnist Rob Walker defined the phrase as an increasingly commonplace computerized mechanism utilized by companies, which scans resumes for key terms to narrow down pools of candidates. This process helps to ensure that job applications are tailored to a specific posting.

As much of the job search process has migrated online, Ann Harrison, communications director at Workforce Alliance in New Haven, says that one of the main points the employment agency stresses to residents is the importance of customizing your resume to the job for which you are applying— to do everything possible to avoid falling prey to tools such as resume optimization in order to make it past the first step of a long process.

However, for residents who come into the agency trying to apply for jobs on their smartphones, this simple step has proven difficult. Harrison says that one of the only effective ways to apply for a job on a smartphone is through Google Drive, which likely requires that you previously worked on documents on a desktop or laptop computer. “The danger with that [using one standard set of application documents] is you are flooding the market with your resume and cover letter that aren’t customized to your job,” she said. Harrison and her colleagues encourage people to take advantage of the computers in the Career Center at Workforce Alliance instead of attempting to edit application materials on handheld devices.

For those who aren’t aware of Workforce Alliance, other employment resources, free technology at the library, don’t have access to transportation, or face other obstacles, smartphones may be the only option when searching and applying for a job.

In the past decade, access to the internet has increased across the board, according to studies by the Pew Research Center. Eighty four percent of adults reported using the internet in 2015 compared to 52 percent in 2000. Although residents who are younger, have higher-incomes and higher levels of education, and are white still have the highest rates of internet use, all groups have seen significant increases in the percentage of respondents who report using the internet.

However, these statistics come with a major caveat: they include the number of residents who can only access the internet using a smartphone or who have limited other options besides their smartphone to access the internet— what Pew calls the “smartphone-dependent” population. Although cheaper and more portable, the handheld devices, with their small size and unique operating systems, don’t offer the same features as a desktop or laptop computer and put users at a disadvantage when applying for jobs. According to one study by Pew, half of Americans who have used a smart phone in their job search have encountered problems, including content not displaying properly or trouble entering a large amount of text.

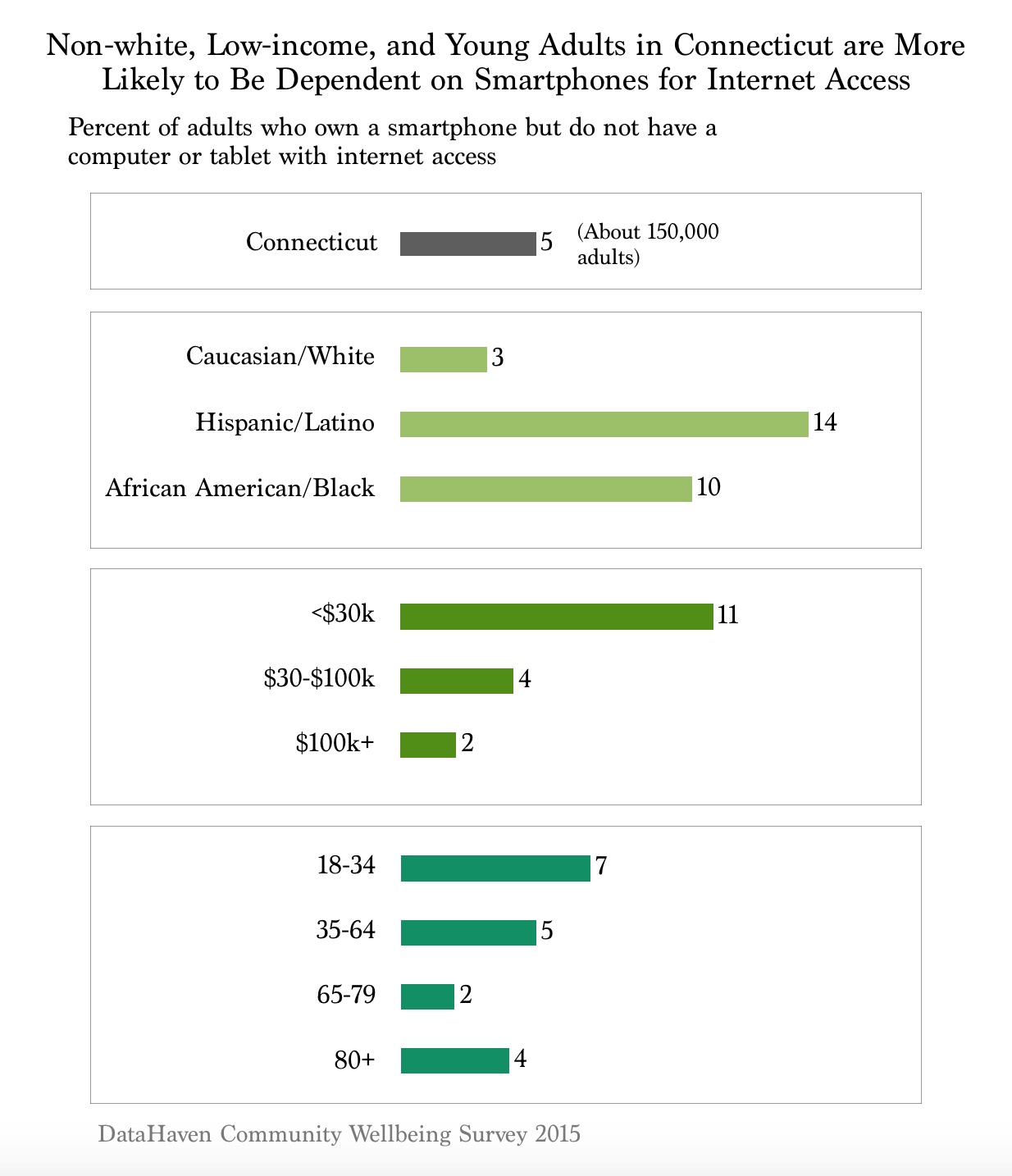

Recent research by DataHaven, as part of its 2015 Community Wellbeing Survey, shows how disparities in access to information shape the digital employment divide in Connecticut.

“There are quite wide differences in resident’s access to broadband,” says Mark Abraham, executive director of DataHaven. “Many young adults are reliant on their smartphones…From a communications and employment perspective, but also as one of the inequities in access to information that relates to household wealth, I think this is an important issue.”

Based on in-depth interviews with more than 16,000 randomly selected adults throughout Connecticut, DataHaven found that 71 percent of the state’s adult population has a smartphone. However, perhaps the more telling statistic is the 5 percent of adults who own a smartphone but do not have a computer or tablet with internet access. Only 3 percent of whites in the state fall into this category compared to 10 percent of blacks and 14 percent of those identifying as Hispanic or Latino. In addition, 7 percent of adults ages 18 to 34 and 11 percent of those from households earning less than $30,000 have smartphones but do not have computers or tablets with internet access.

The state’s major cities, including New Haven, Bridgeport, and Hartford have some of the highest rates of smartphone-dependence, according to the results of DataHaven’s survey. Smartphone dependence also poses significant problems for children working on homework, however the survey only included residents age 18 and older.

A comparison with national data suggests that Connecticut’s trends are similar but that overall a smaller percentage of people in the state are smartphone-dependent compared to the rest of the country. According to Pew, 10 percent of Americans own a smartphone but don’t have any other form of high-speed internet at home. Thirteen percent of Americans with an annual household income of less than $30,000 are smartphone-dependent, 15 percent of Americans age 18 to 29 are “heavily dependent” on a smartphone for internet, and 12 percent of African Americans, 13 percent of Latinos, and 4 percent of whites are smartphone-dependent.

This reliance on smartphones is not motivated by a growing disinterest in broadband — Pew found that compared to 2010, when 48 percent of Americans without a high-speed internet connection at home said it was a major disadvantage not to have broadband, in 2015, 65 percent of non-broadband households said the same. Cost serves as one of the main barriers to accessing high-speed internet at home, according to Pew.

Connecticut’s lower overall smartphone reliance could be explained in part by the state’s higher average income. However, when broken down by race, age, and income, comparable percentages of non-white and low-income residents are affected as at the national level.

For populations already plagued by high underemployment rates, the reliance on smartphones may further exacerbate low rates of employment.

“There really are no shortcuts,” Harrison says. “You still have to do all of the things that you would normally do [with a job application that is not online].”

Harrison says there are a few ways smartphones can be used to benefit job seekers, but even these have limits. She says that some residents who come into Workforce Alliance sign up for job alerts on their phones. The initial alert is helpful; however, taking further steps on a smartphone puts users at a disadvantage. Often sites that offer these alerts, aggregate sites such as indeed.com, may show a job posting that is no longer available or that appears in a different format than on the company’s website.

Ashley Sklar, the community engagement and communications manager at the New Haven Free Public Library, has found trends similar to those explained by Harrison. Residents applying for jobs sometimes show up to the main library and other local branches asking for help creating or accessing a document on their smartphones. Often they are equipped with a paper resume or flash drive. She says that once an individual has consulted with a librarian, they quickly switch to working on one of the library’s computers to complete the application, finding it a much easier task.

Sklar’s experience is one example of the evolving role of libraries as places of public programming, career resources, and community gatherings. According to a recent report by TrendCT, since 2001, the number of programs offered by libraries in the state has almost doubled while the number of instances of book-loaning and computer use have stayed the same or decreased.

Sharon Lovett-Graff, the Mitchell Branch manager for the New Haven library system, says although there has been a decrease in demand as more people have been bringing in laptops to use the library’s free Wi-Fi, computers for adult users still fill up fast. Sklar recalled one instance where a mother wasn’t able to print a project before the library closed. When the user asked for another place she might go to finish, “It was a struggle to name another free public resource where she could complete her project, exemplifying the privatization of personal technology and the emergence of the assumption that everyone has their own tech,” Sklar said.

The main library is open from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m Monday through Thursday and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Friday and Saturday. The Workforce Alliance Career Center is open from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Monday through Friday.

Both Harrison and Sklar say that there are some, but not a huge number of residents who come in seeking help on their smartphones, suggesting that more outreach to the population that is relying on their smartphones to conduct job searches and other necessary processes may be necessary.

The NHFPL has plans in the works to reach out to the smartphone-dependent population. Current outreach efforts are more focused on computer and internet training and education.

Emma Zehner is a Williams College student who is working as a summer research intern at DataHaven.