All DataHaven Programs, Civic Vitality, Community Wellbeing Survey

Lively town hall meeting at Old State House explores Connecticut data on civic engagement

BY EMMA ZEHNER

Residents gathered in the Old State House in Hartford on June 9 to discuss the future of civic health in Connecticut. CT-N’s program, “Great Citizenship: Building a Better Connecticut,” centered on the results of the 2016 Civic Health Index Report and featured several prepared statements from state and local leaders. Throughout the night, panelists and audience members grappled with explanations of and potential solutions to the disparities in civic engagement across different socioeconomic groups within Connecticut, with a particular focus on differences in voter turnout.

“We all know that we hear lots of news today about dissatisfaction and about what it is to live in Connecticut and how does it feel to live in Connecticut,” Martha McCoy, Director of Everyday Democracy, said to the audience in her opening statement. “Something very important is often missing from those conversations and these polls and that is the notion of civic health… So in a place that has good civic health, what does that look like? There are places and habits and supports for people to work with each other, work across difference, have a difference, to vote, but also to struggle together and to have tough conversations together and to take action together.”

The 2016 Civic Health Index Report, published in January, builds on a similar survey completed in 2011, which measured statewide civic participation. For the updated report, DataHaven partnered with the National Conference on Citizenship, Everyday Democracy, Secretary of State Denise Merrill, and other members of the Connecticut Civic Health Advisory Group to survey state residents about their volunteering and voting habits. The study found that for indicators including attending public meetings, giving to charitable organizations, and voting in local elections, Connecticut performed well, while the state had a less impressive record for indicators such as registering to vote in national elections, belonging to a school or community association, or joining a church group or other religious group. However, most measures varied dramatically by income, race and ethnicity, and educational background.

Bilal Sekou, associate professor of political science at the University of Hartford, who sat on the panel, said, “On a number of indicators, the state was in the middle of the pack. I was kind of surprised by that, but then I think when you look at the total picture, and this is where the income and the race and the other inequalities in the state actually contribute to what the state lags behind on some of those indicators…This study really provides us with some key insights into some of the systemic and deeply rooted challenges we face in a society that calls itself a democratic society.”

Following several opening remarks by the panelists, moderator Diane Smith turned the program to a discussion of voting by projecting several graphics featuring the findings of the 2016 report.

First, she introduced a bar graph showing voter participation by race/ethnicity in the 2012 presidential election: 66, 62, and 47 percent of Whites, African Americans, and Latinos voted respectively. These rates are similar to those of the country overall: 66, 64, and 48 of African Americans, Whites, and Hispanics in the United States voted during the same election. (http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/05/08/six-take-aways-from-the-census-bureaus-voting-report/)

Alma Maya, a community organizer and former Bridgeport town clerk, responded to the state’s statistic.

“I think that if we want Latinos to vote, we have to invite them in and educate them on why it is important for them to talk about the little things that impact their daily life…people have said to me well how is that going to change my life? And sometimes it doesn’t. It really doesn’t. If I vote for president, is that really going to change anything? So trying to get them engaged on a local level I think is more important. That’s really going to change things for you and I think that is where we need to begin. Start locally.”

Next, Smith projected a graph showing that in the same presidential election, fewer than half of people aged 18-24 in Connecticut voted while two-thirds of people 25 and older voted. Nationally, the U.S. Census Bureau report said, 38 percent of people in this age category voted in the 2012 election, which is slightly lower than the state’s rate. (https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p20-573.pdf)

Sekou offered one explanation. “If you’re a young, unemployed in a city, you may see the government not responding to your interests, that idea that you would get engaged and be voting I think becomes more and more remote regardless of how much civic education you receive.” He recommended that we take steps to make it more convenient for young people to vote, including providing places to vote on campus and allowing student IDs to count as identification.

He also cautioned against talking about millennials as one monolithic group when in reality, within this age demographic, there are stark differences in access to the technology that facilitates opportunities for engagement and leads to good measures of civic health. Recent research by DataHaven in the 2015 Community Wellbeing Survey shows that in addition to disparities by age, computer and smartphone ownership are unequal across race, income level, and education level.

Other panelists and audience members discussed the pressing need to revamp the current civics program in Connecticut public schools as a way to increase rates of participation among younger age demographics. Keynote speaker and author of The Gardens of Democracy Eric Liu said that we need to “Make it explicitly and unabashedly about power. Who has a voice and why? Who doesn’t and why not? Literacy and power. I can get excited about that. Action. Practice is what matters so fundamentally. Learn by doing. Learn about civics by doing.”

Stephen Armstrong, a Social Studies Consultant for the Bureau of Teaching and Learning in State Department of Education commented on a recent visit to a public school. When he sat in on a class, students were taking a quiz about the departments of the federal government.

“I can assure you that they were not jumping up and down with excitement when they were answering those quizzes,” Armstrong said. “We think that if we just teach kids more facts about government, that will create citizens…Schools should be places where kids practice citizenship.”

Armstrong played a key role in incorporating civic engagement and civic action components into the new Connecticut Social Studies Framework.

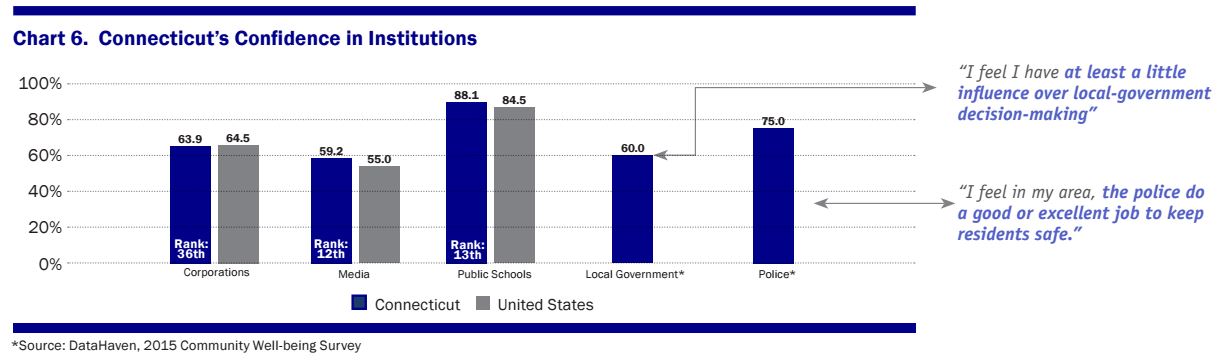

Throughout the night, Smith referenced several other findings of the Civic Health Report, including lower voter turnout for residents with lower levels of education and income. She also touched on data showing that Connecticut residents were relatively confident in public schools and the media compared to other states but lacked confidence in corporations.

Other attendees commented on the role of voting in our country’s system of mass incarceration as well as the role of new technology in the development of modern citizens.

Liu offered a closing remark. “We have to start thinking about the world as if we are epidemiologists, but instead of looking at the map of our community and thinking oh where’s the flu outbreak? what are the nodes? what are the households where…all these bad things are happening? We have to look at where are the nodes where good things are happening? Where are the nodes where volunteerism is happening? How may we amplify and accelerate those?”

The program concluded with a few words from Elena Tipton, who is Connecticut’s 2015-2016 Kid Governor and a representative of one of the state’s efforts to increase youth participation in local government.

“Great Citizenship: Building a Better Connecticut” was made possible thanks to generous funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, CT Humanities, the William Caspar Graustein Memorial Fund, and Connecticut Campus Compact. Emma Zehner is a summer research intern at DataHaven.