[Excerpt from November 27, 2019 Hartford Guardian article by Christian Spencer]

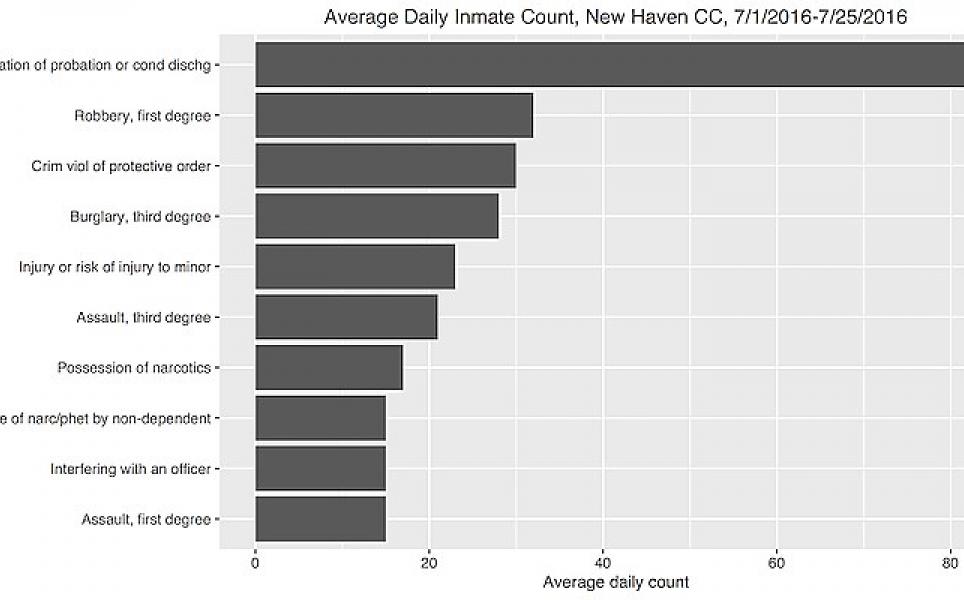

[....] Every year, more than 11 million people move through America’s 3,100 local jails and prisons, many on low-level, non-violent misdemeanors, costing local governments about $22 billion a year, according to a 2016 White House initiative. In local jails and prisons in Connecticut, about 550 people were in pre-trial detention. Some of these pre-trial detentions are because of the politics of race or dire poverty. In both cases, the detainee has to stay in prison until he can afford bail.

To break the cycle of incarceration and wealth-based jailing, President Barack Obama’s administration launched the Data-Driven Justice Initiative with a bipartisan coalition of 67 city, county, and state governments, who have committed to using data-driven strategies to divert low-level offenders with mental illness out of the criminal justice system and change approaches to pre-trial incarceration, so that low-risk offenders no longer stay in jail simply because they cannot afford a bond.

[....]

Connecticut joined in on the DDJ initiative. Former Gov. Dannel P. Malloy’s administration launched its Second Chance Society initiative, signed into law in 2016, to decrease both incarceration and crime rates; a second set of proposals targeted bail and pretrial detention. But it did not pass into law. It’s unclear whether Gov. Ned Lammont will continue with this initiative.

[....]

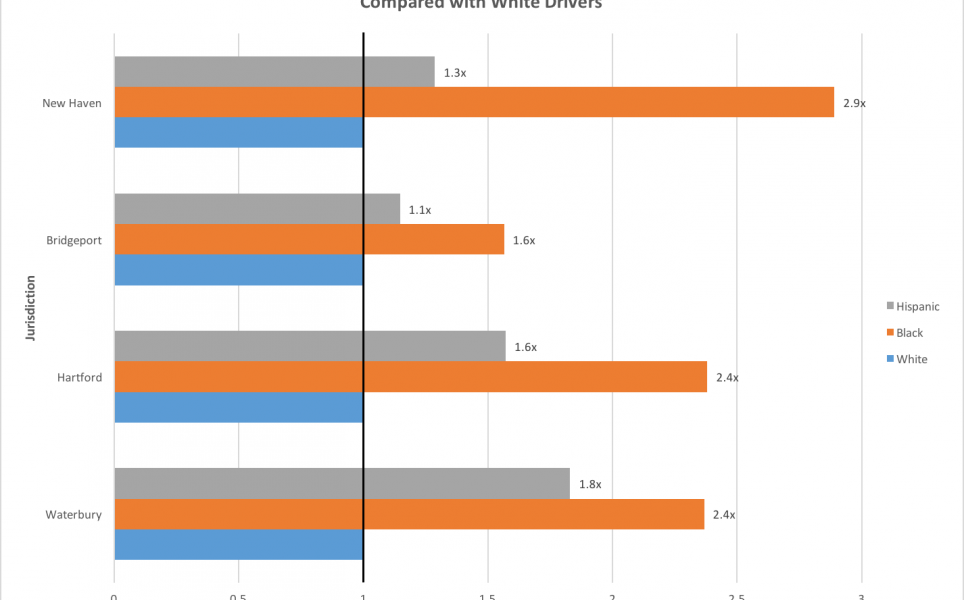

While prison rates have stalled and begun to decrease slightly for people convicted of and sentenced for crimes, a high—and increasing — number of people are detained in jails without conviction, according to Camille Seaberry of DataHaven. Many of these people have cycled repeatedly in and out of jail and prisons. Some are being charged only with nonviolent misdemeanors. African-Americans and Latinos are held in pretrial detention at much higher rates than white people.

In New Haven, African Americans make up 33 percent of the population but 56 percent of custodial arrests—and similar disparities exist in Bridgeport and Hartford.

There is even evidence that the length of time spent in detention before trial may predict whether a person is sentenced to prison and for how long. There is also a growing movement toward more data-driven practices within criminal justice systems, such as risk assessments, though this is not without its concerns of bias, according to Seaberry. [....]