Demographics, Economy, Health

Reduce the risks of reopening for Black and Latino workers

Reduce the risks of reopening for Black and Latino workers

By Nathan Kim and Cynthia Farrar

The dilemma of reopening is often framed as a choice between public health and economic growth, between life and livelihood. But for families like Aziya’s, the trade-off is not so clearcut. Because of a long history of occupational segregation, working is riskier to their health, and the economic rewards are limited and insecure.

Aziya’s realistic assessment of their options opens the final episode of COVID-19 Reckonings, a video series produced by Purple States and DataHaven with residents of Connecticut communities where infection and death rates have been especially high due to long-standing social and economic inequities. In the economic as in other dimensions of the pandemic, an acute problem for white families is both more acute and chronic for Blacks and Latinos. As the title of the final episode suggests, they now face tougher choices.

For some workers, the reopening requires no trade-offs. According to the Economic Policy Institute, higher-wage workers are six times more likely to be able to work from home than lower-wage workers. And they are clustered in particular industries. A National Bureau of Economic Research working paper reports that 75 percent of finance, management, and education sector employees can work remotely, as compared to 4 percent of hotel and food service workers. In its recent health equity report, DataHaven draws on its analysis of the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to show that workers who must either start or — as ‘pandemic-essential’ workers — continue going out to work are disproportionately people of color, while the workers who can work from home are disproportionately white.

Occupational segregation into certain industries means disproportionate risk of exposure. Black and Latino workers are more exposed to infections not just because they have to go out to work to support their families, but because they are overrepresented in particular sectors. A new study of 2019 national employment statistics by occupational risk factors finds that Black workers are over-represented not just among ‘essential’ workers in the sense used during the pandemic shut-down, but in all industries that involve close contact with other workers and the public.

The jobs of the people featured in COVID-19 Reckonings fit a cluster of Department of Labor/Occupational Information Network (O*NET) criteria that defined what we now call frontline work well before the pandemic: daily physical proximity, contact with others, and exposure to disease and infections. Jobs with these characteristics include the roles deemed ‘essential’ during the shutdown, and many others in sectors that are now reopening. Aziya’s godmother is a security guard; Tyrone is a chef; and Tank has been working throughout the pandemic, performing the ‘essential’ work of sanitation at a big-box grocery and retail store.

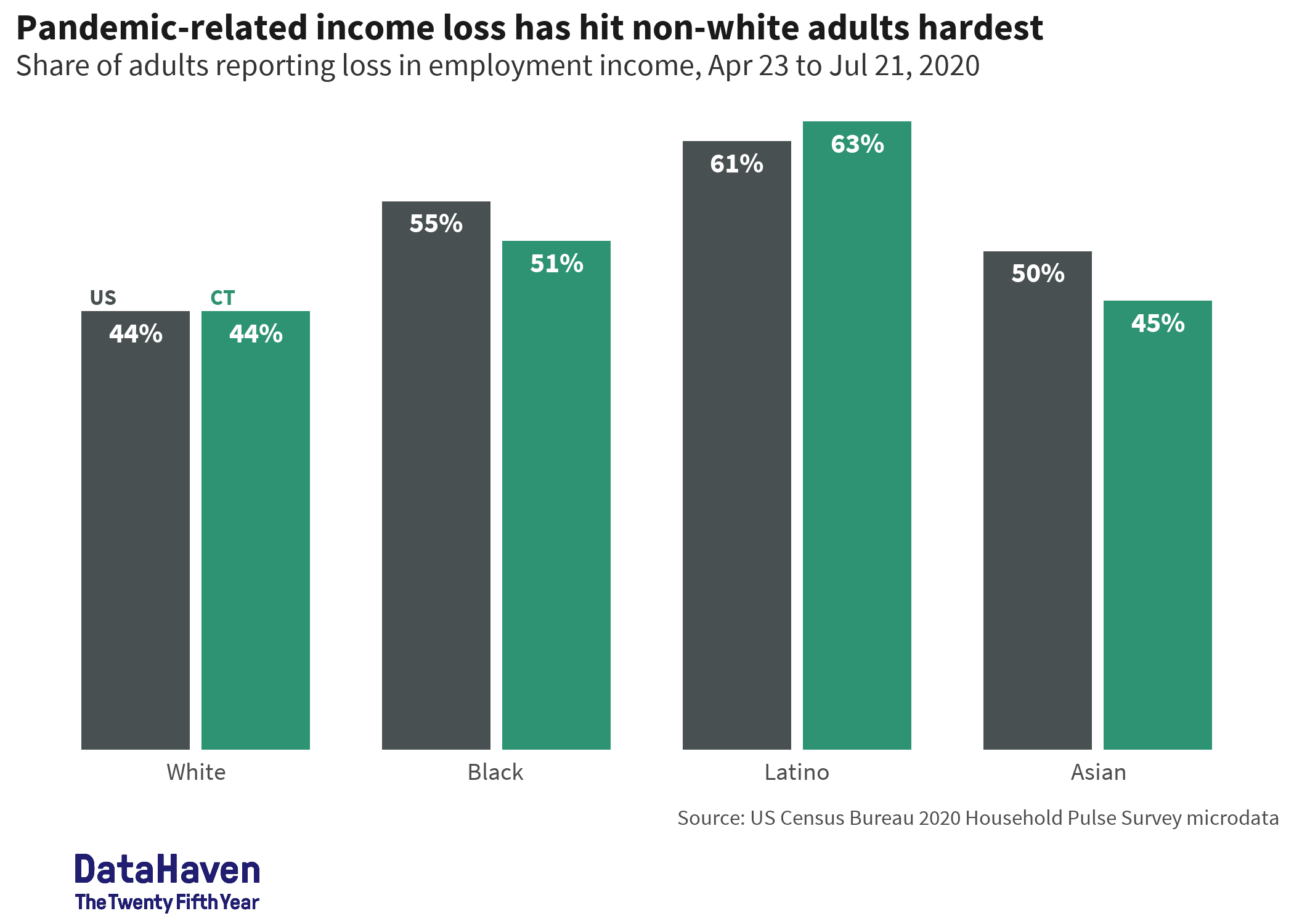

These workers face greater health risks because of the kind of work they do. But they are also more likely to lose their jobs. In Connecticut, Black and Latino workers have been hit hardest by the economic impact of the lockdown measures. According to DataHaven’s analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 24 percent of Black workers in Connecticut reported a job loss during the pandemic compared to 11 percent of white workers. Additionally, 30 percent of white workers in Connecticut who stopped working said they were furloughed or laid off, or a business had closed, temporarily or permanently – as opposed to 48 percent of Black workers and 47 percent of Latino workers.

What happened during the shutdown is a sign of persistent job insecurity. Even before the pandemic, workers in these sectors have been more likely to lose their jobs. The DataHaven analysis cited above shows that industries at high-risk for job loss include retail, food service, and personal care — like beauty salons and barbershops.

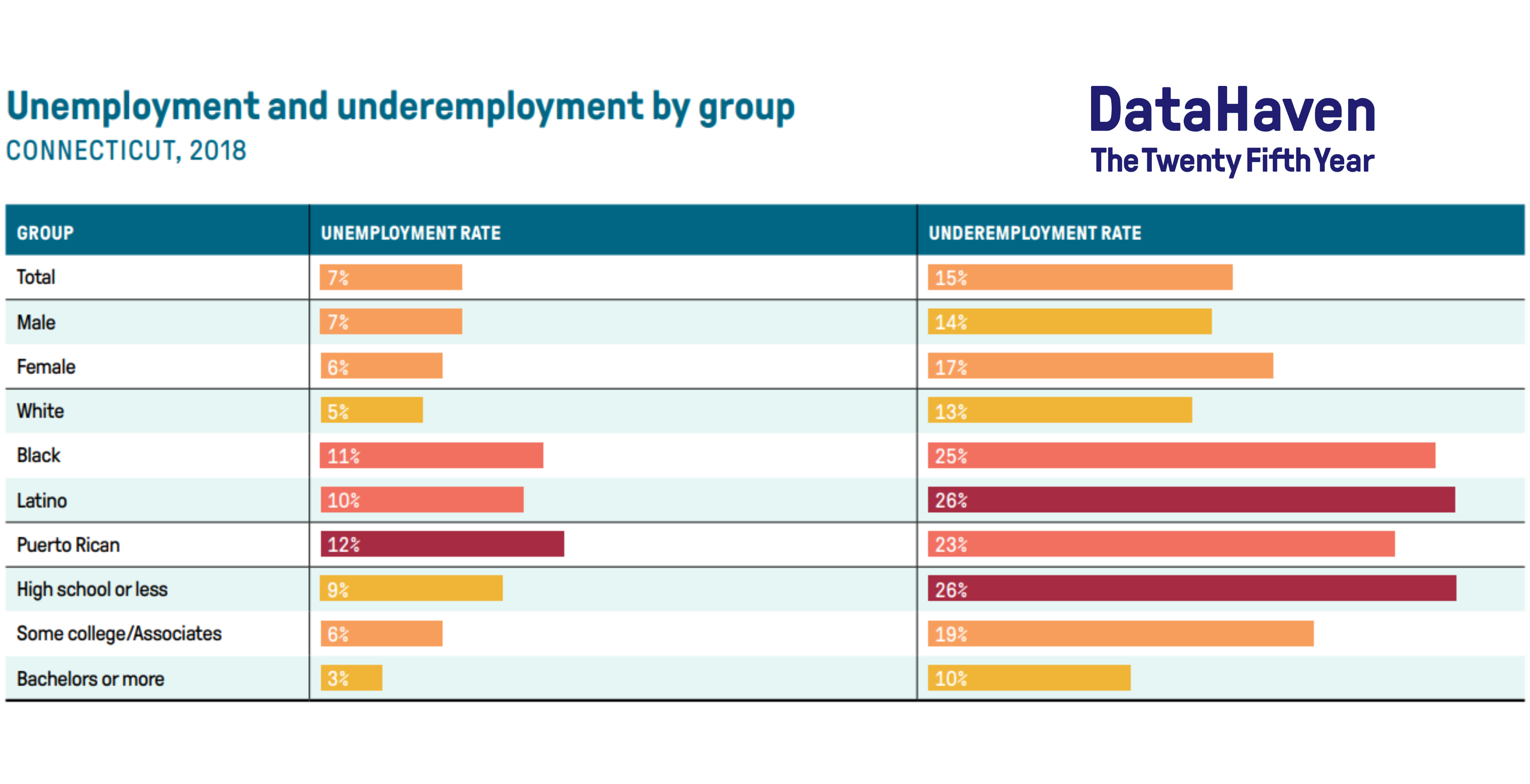

Persistent inequities in employment, income, and wealth have deepened the difficulties faced by people of color during the pandemic. Black and Latino workers in Connecticut were already twice as likely as white workers to be unemployed or underemployed. And Black and Latino households often have little or no financial cushion to buffer the consequences of a period of unemployment. National Census data shows that for every $100 of wealth held by whites, Black and Latino families possess only about $10. A Prosperity Now analysis of Census data from 2013 to 2017 estimated that 56 percent of households of color in Connecticut did not have enough wealth to cover basic expenses for three months if they lost their primary source of income. The same was true for only 19 percent of white households.

DataHaven analyses of surveys collected by the Census Bureau since March 13th confirm this picture. Without savings or assets to cushion against the worst effects of the shutdown, many residents have been unable to pay for even basic necessities. Black and Latino residents in Connecticut were over two and a half times more likely than white residents to be unsure of how to pay rent or mortgage during the pandemic, at 31 percent, 34 percent and 12 percent, respectively. In this same period, Black and Latino residents of Connecticut were also three times as likely as white residents to face food scarcity in their households, at 18 percent, 18 percent, and 6 percent.

Dismantling the entrenched racial inequities that have for so long restricted opportunity and heightened risk for Black and Latino residents of Connecticut will require structural reform. In the short term, rent moratoriums, stimulus checks, and more funding and flexibility for safety net programs can help residents meet their basic needs. Assistance to employers in securing protective gear (PPE) for everyone whose job involves proximity to others is crucial to protecting workers during the reopening. But the ways the individuals featured in Tougher Choices are responding to their quandary also point to two intermediate steps local and state stakeholders could take during the uncertain months ahead. During a time of gradual reopening and slow recovery from recession, these actions can help residents find a more sustainable solution to this double threat of health risk and economic insecurity.

Support entrepreneurship. Tyrone is trying to reimagine his career in a risky sector to create a viable and less-vulnerable business, and build intergenerational wealth. In New Haven, a local coalition that includes the Community Foundation and the City and an Economic Justice Fund started by ConnCAT are offering loans to make up for the federal government’s inadequate support for minority-owned businesses like Tyrone’s.

Protect municipal employment. In his search for a better, more secure job, Tank is applying to the City of Hartford. Government jobs have long been a ladder to opportunity. Yet city jobs are likely to shrink because the pandemic is already affecting tax revenues and expenditures, state and local, as the Connecticut Mirror recently reported.

In time, this crisis will recede for most residents of Connecticut. But the inequities it exposed and exacerbated will persist for Black and Latino families. In a June 2020 Washington Post/Ipsos poll, 83 percent of Black Americans said that controlling the virus is a higher priority than restarting the economy, compared to half of white Americans. In light of the experiences of the individuals featured in COVID-19 Reckonings, this is unsurprising. And not only because housing segregation increases the chances of infection; or because limited access to healthy food and high-quality health care raises the odds of serious complications. Without structural change in a variety of interlocking contexts, including housing segregation and the funding of education, Black and Latino residents will remain concentrated in jobs that jeopardize their health and won’t lead to financial security. This is not just a tougher choice — it’s no-win.

Nathan Kim is at DataHaven, a non-profit organization with a 25-year history of public service to Connecticut communities. Its mission is to empower people to create thriving communities by collecting and ensuring access to data on well-being, equity, and quality of life.

Cynthia Farrar is at Purple States, a video production company that brings the voices and stories of individuals affected by an issue into public discussion of what’s at stake and what should be done. Purple States has produced video for national news organizations and for a Connecticut news collaborative, the Cities Project.