All DataHaven Programs, Civic Vitality, Demographics, Economy

At risk: Fair and valid census data for Connecticut

[note: This article by DataHaven staff originally appeared in the Connecticut Mirror, at https://ctviewpoints.org/2017/10/02/at-risk-fair-and-valid-census-data-for-connecticut/]

By Aparna Nathan and Mark Abraham, DataHaven

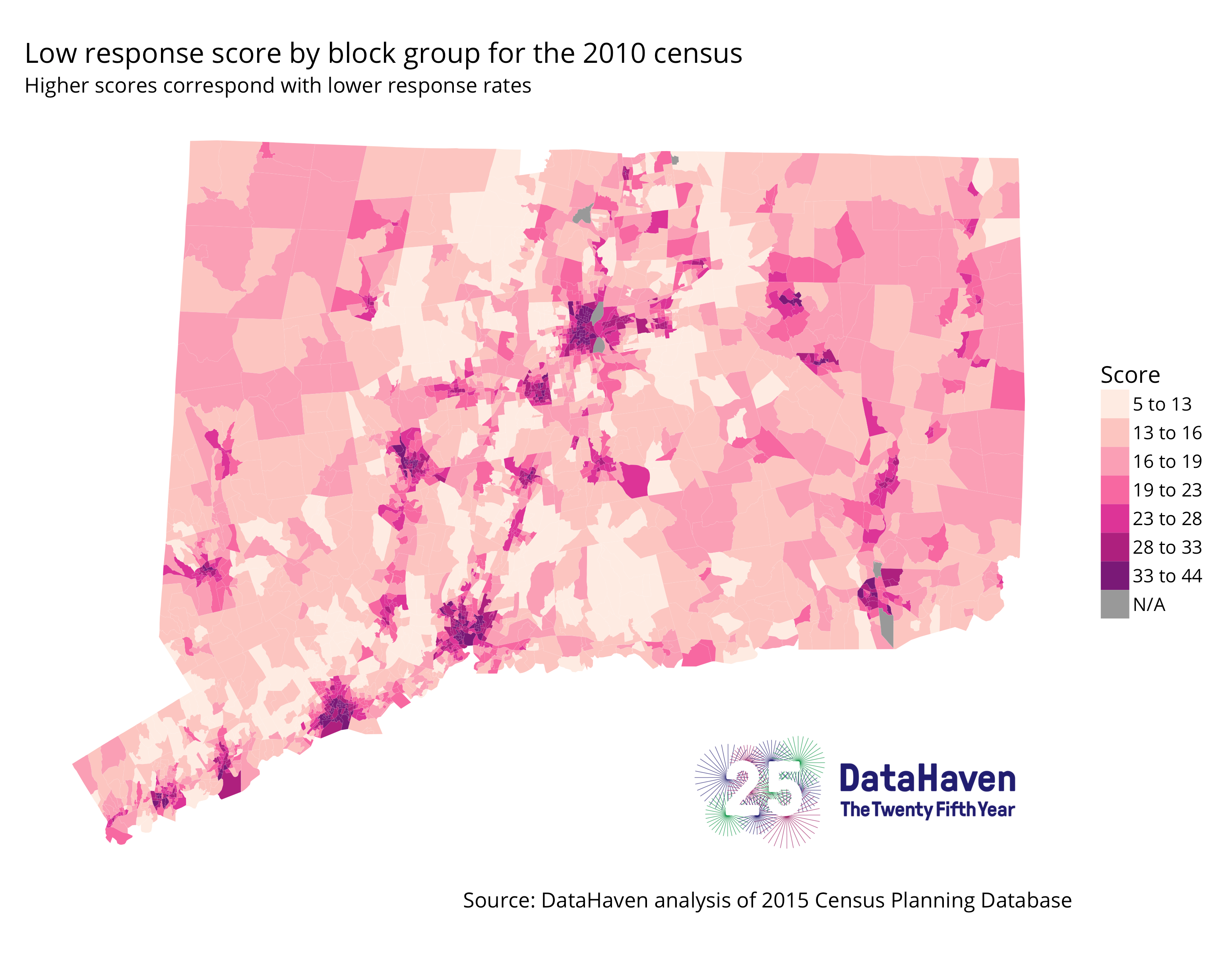

Map of areas with low mail response rates to the 2010 Census questionnaire. Source: DataHaven analysis of Connecticut data in the 2014 Census Planning Database.

The 2020 Census could be in jeopardy—and it could hit close to home in Connecticut.

The right to equal representation for equal numbers of people is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment; though imperfect, this is the basis of our democratic system. The Constitution requires that every ten years, the nation undertakes what is arguably its most essential task: ensuring a fair and valid count of every single one of its now 330 million residents.

The decennial census is a feat of manpower, logistics, and advertising. Mailings are sent to every household in the country, and Census Bureau field workers go door to door to collect information from non-respondents. The products of these efforts are data sets that characterize our population, create political districts, and enable virtually all other ongoing data collection efforts. Among the projects made possible by the decennial census are the American Community Survey, which determines the distribution of hundreds of billions of dollars worth of annual government expenditures, and the DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey, a statewide effort of over 100 partner organizations to track neighborhood-level quality of life and well-being.

Counting dollars, counting people

Carrying out the decennial census understandably requires a significant investment. Given its importance to all other operations of government, however, the census is arguably one of the most cost-effective federal programs. Funding for the Census Bureau is appropriated by Congress for each fiscal year.

Typically, as the Census Bureau figures out the real cost of each stage of planning and execution, Congress adjusts the projected budget for the census, says Terri Ann Lowenthal, a consultant and former congressional staffer who directed the House’s census oversight subcommittee and now lives in Stamford, Connecticut.

But, this is the first time in modern history that a census has had an upfront cap on its total spending, Lowenthal says. In 2012, Congress told the Census Bureau to spend no more than they spent on the 2010 Census, and even encouraged them to spend less. Carrying out the same operation as in 2010 would cost a projected $17.8 billion overall, but the 2020 Census Operational Plan aims for $12.5 billion.

According to the 2020 Census Operational Plan, these lower projections reflect the amount of human outreach required. In the past, field workers have gone door to door before the census to check addresses, and then again after the forms have been mailed out to follow up with the significant number of non-responding households. Looking forward to 2020, the Bureau has been planning technology and communications strategies to minimize the required manpower. For example, existing data and satellite imagery will help verify lists of addresses, and respondents will be able to fill out the short questionnaire online, by phone, or using a paper form, to make it as convenient as possible.

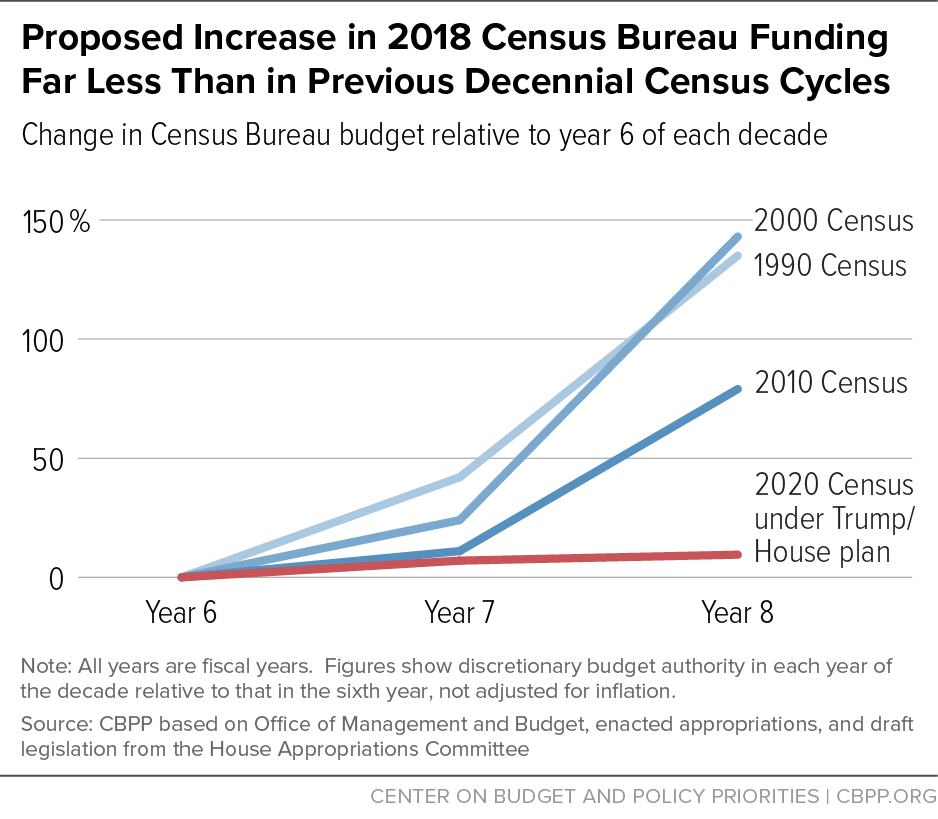

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, cbpp.org

Unfortunately, so far, Congress has not even been meeting the scaled-back funding requests of the Census Bureau. The Bureau originally requested $1.64 billion for fiscal year 2017, but the budget passed in April only granted them $1.47 billion. The new administration requested just $1.497 billion for fiscal year 2018, which pales in comparison to the 60 percent increase that was provided between fiscal years 2007 and 2008 leading up to the 2010 Census, or the near doubling between fiscal years 1997 and 1998 leading up to the 2000 Census.

“The funding for the Census Bureau needs to ramp up sharply,” Lowenthal says, noting that this is especially true in the final three years leading up to the census.

Tests canceled and Communications Delayed

The lack of funding and delayed budget approvals are already having a broader impact than intended. As Congress has tightened the purse strings, the Census Bureau canceled its 2017 field tests in Washington, the Dakotas, and Puerto Rico. In a memo written last year, Lisa Blumerman, an associate director at the Bureau, wrote that the Bureau “will not continue expending resources to prepare for the FY 2017 field tests,” given the insufficient resources to conduct them. They said they would instead direct their efforts toward the End-to-End Census Tests in 2018, a sort of dress rehearsal, Lowenthal says, that allows the Bureau to test every step of the administration process.

Since then, the Bureau cancelled two of the three intended 2018 tests of the full operations in a suburban Washington county (a site that includes a Native American reservation) and a rural region in West Virginia. This leaves one final End-to-End Test in urban Providence, Rhode Island, but it means that they won’t get the opportunity to make sure their targeted outreach is working in rural areas or on reservations, not to mention the lost chance to test their bilingual offerings in the canceled 2017 test in Puerto Rico.

Those tests could have been relevant to the 2020 count in Connecticut, both in rural areas and cities such as Hartford with large Spanish-speaking populations.

According to Lowenthal, the Census Bureau is also lagging behind on its communications plan, which includes the research and design of targeted messaging to reach populations that are considered to be “hard to count.” At this point, just three years away from the actual administration of the 2020 Census, outreach is everything.

“Hard to count” is a term that includes African American and Hispanic households, non-English speakers, low-income families, renters or people living in transient housing, immigrants, and college students. These are populations that typically have low response rates for the decennial census for varying reasons, says Anna Mariotti, who worked as a partnership specialist with the 2010 Census in Connecticut.

The risk of undercounting Connecticut residents

An underfunded 2020 Census is likely to systematically undercount some of the state’s more vulnerable populations and undermine efforts to create a more equitable, opportunity-rich state. This is particularly concerning given the end purpose of census data. Since population distributions are used to draw voting districts and determine the number of representatives each state or neighborhood gets in our legislative bodies, undercounting hard-to-count groups means that their vote may count less and their voice might not be heard at the state level or in Congress.

In Connecticut, many groups could be susceptible to an undercount if they don’t receive sufficient outreach. For example, sizeable immigrant populations throughout much of the state, and refugee populations in Hartford and New Haven, might find themselves questioning the confidentiality and importance of the census, especially in the current climate of fear and anti-immigrant rhetoric, Lowenthal says.

“Communities that feel threatened by the government right now—racial/ethnic minorities, particularly immigrant families—will be less likely to fill out or answer detailed questions in response to queries by government workers,” agrees Sharon Langer, advocacy director at Connecticut Voices for Children, a nonprofit that advocates for policies that benefit children and families in the state.

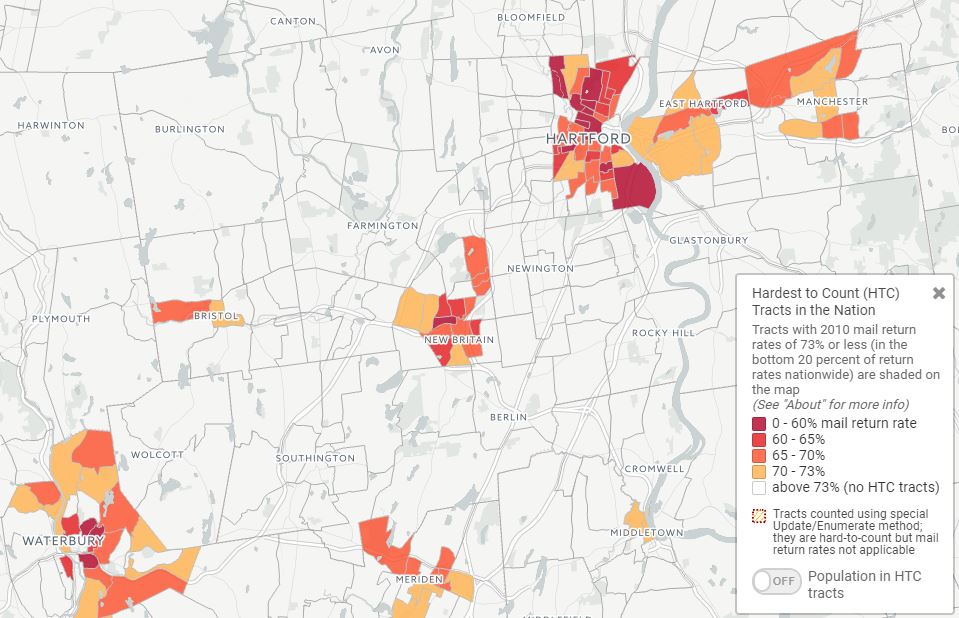

Spanish-speaking populations in Hartford and New Haven, and Polish-speaking populations in New Britain, might also find the 2020 Census to be less accessible than hoped. Structural challenges are a concern as well: Hartford also has some of the lowest homeownership rates in the state, at about 24 percent, and much of its population is living in unstable housing, making it more challenging to ensure that everyone is counted at their current addresses.

If low-income families are undercounted, Connecticut will receive less funding from Washington to support critical public assistance programs like Medicaid, Medicare, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and housing assistance.

During the 2010 Census, Connecticut managed to reach a 74 percent mail response rate, surpassing the nationwide rate of 72 percent. Connecticut was the 15th highest responding state, and led the rest of its New England neighbors.

But this wasn’t representative of all parts of the state. In particular, Connecticut’s large cities tended to have lower mail response rates. In the final days leading up to 2010’s Census Day, the Census Bureau announced its concern that Bridgeport, New Haven, and Hartford, in particular, were nowhere near their response rates from 2000. By the end of the 2010 Census, the Connecticut neighborhoods with the lowest two percent of mail response rates statewide were all concentrated in the largest cities in Connecticut (Bridgeport, New Haven, Hartford, Stamford, Waterbury, and New Britain). Their response rates ranged from 41 percent to 56 percent, meaning that census takers had to try to track down residents during the far more costly door to door operation in order to eventually achieve what these communities hoped would be as close to a complete count as possible.

It’s not surprising that Connecticut’s cities are particularly vulnerable, Langer says. These neighborhoods—“block groups,” in census jargon—with low response rates have demographics that match up to hard-to-count populations. Places with lower response rates had more African American and Hispanic residents (by almost 30 percentage points), as well as more non-English speakers and renters. On average, 82 percent of residents in each of the bottom two percent of low self-response block groups were renters, compared to 14 percent in the rest of the block groups. In some areas of Connecticut, the share of renter households and Latino residents has grown significantly since 2010.

Implications on Connecticut cities and towns

“Hard to count” areas in central Connecticut. Source: Census 2020 HTC Map application, CUNY Center for Urban Research, http://www.censushardtocountmaps2020.us/.

Connecticut organizations and elected officials interviewed for this article are concerned that the people who stand to benefit the most from programs whose funding is based directly or in part on the 2020 Census will not be fully counted. An undercount, leading to fewer federal dollars, would impact communities as a whole, as well as the state budget.

For example, after Medicaid and Medicare, SNAP benefits brought in the next highest amount of census-based funding, at over $715 million dollars in fiscal year 2015, according to the “Counting for Dollars” project at George Washington University. Large shares of the families in block groups with low mail response rates during the initial phase of the 2010 census are beneficiaries of SNAP and other federally-funded programs. Undercounting these families puts the programs that support them and their communities at risk.

Similarly, Connecticut received $387 million dollars in census-based Section 8 voucher funding in fiscal year 2015. The block groups with the lowest response rates each received housing choice vouchers for an average 37 percent of their households, compared to 17 percent in the rest of Connecticut’s block groups.

Families rely on these programs to have a roof over their head, put food on the table, and ensure good health. But the state is already struggling to maintain the current level of funding for these programs—it has reduced eligibility for HUSKY, for example—and there are limited resources to replace the lost dollars should the census undercount their potential beneficiaries in Connecticut.

Funds for transportation infrastructure are also allocated based on census counts. Mary Ellen Kowalewski, director of policy development and planning at the Capitol Region Council of Governments, says her organization is responsible for planning transportation in the Hartford metro area, and they use census data to ensure that transportation is accessible to the people who need it the most. “There’s a strong desire for equitable development within our regional plan,” Kowalewski says. “Census data helps our staff identify critical needs.”

Even the enforcement of civil rights laws, and other programs tied to the protection of the rights of minorities, are also linked to census data. Groups that have historically been threatened by disenfranchisement, hate crimes, lending discrimination, and other forms of oppression could be at greater risk if they are not represented with accurate data. For this reason, LGBT advocates were disappointed when the Census Bureau recently decided to drop questions about gender identity.

Nonprofits are also major users of census data, because it helps them pinpoint real needs, says Scott Gaul, director of research and the Community Indicators Project at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.

A Call to Action

What will it take to revitalize the 2020 Census and correct the oversights of the 2010 one? Adequate funding, Lowenthal says. She acknowledges that the constraints on the federal budget are significant but there is a chance that Congress will re-evaluate its stringent budget for the Census Bureau.

National networks of businesses, advocates, institutions, and government agencies, such as The Census Project, are actively encouraging Congress to allocate the resources necessary to produce fair and accurate census data.

“In the past, Congress has come up with funds at the eleventh hour. They realized, when push comes to shove, in the years ending in 9 and 0, that they have a lot at stake and the most to lose at the possibility of a failed census,” Lowenthal says. “But we don’t yet have any signs that Congress is going to loosen those purse strings significantly.”

If the resources won’t come from the federal government, it could come from other entities instead. Some states allocate additional funds for census outreach efforts, but it doesn’t look promising in Connecticut, given current budget woes. Mayors and city councils may be asked to play a larger role as concerns mount. At the local and regional level, various institutions and agencies, coupled with leadership from grassroots organizations that represent hard-to-count groups, could collaborate to develop more effective, data-driven outreach within available resource constraints.

Another step is to look to philanthropy. The Funders Census Initiative aims to bring in money to supplement inadequate federal funding to ensure an accurate census count. Gaul says the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving has demonstrated interest in the Initiative, and they have also discussed how they can make sure census takers reach all the demographic groups in their region, especially those of greatest need.

“We need boots on the ground and outreach to do what we can to reach those groups,” Gaul says.

Other funders have echoed this concern, and organizations like the United Philanthropy Forum and Annie E. Casey Foundation have recently published resources and guidance on how communities can help ensure a valid 2020 count. Funders have a lot at stake, especially in their own communities where the Census Bureau may need more money than anticipated to hire people to staff partnership programs that specifically target hard-to-count populations. This could mean putting reminders about the Census on church newsletters, including messaging about the census on monthly utility bills, or working with local grassroots organizations.

Lowenthal estimates that, during the 2010 Census, philanthropy brought in at least $34 million dollars to fund these campaigns—an important step, but nowhere near the amount needed nationally.

“Philanthropy can only do so much in filling the gaps, and does not have the resources to fill large gaps,” Langer says.

As a partnership specialist during the 2010 Census, Mariotti knows just how important outreach is. For the 2010 Census, Mariotti began outreach efforts the year prior, specifically collaborating with colleges across the state to make sure that students filled out the census for their Connecticut addresses. She also worked in New Haven, where she connected with grassroots organizations like Junta for Progressive Action and Unidad Latina en Acción, as well as the NAACP, to build trust and educate people about the census and its purpose.

“I think not educating people—not doing the outreach or letting people know the importance of the census and what it means for their community—still has the potential to make a big negative impact on the response rate,” Mariotti says.

While the continued limitations on federal resources may make a complete count more challenging than ever before, local mobilization may help mitigate the potential harm to Connecticut’s residents and neighborhoods.

Aparna Nathan is Research Assistant and Mark Abraham is Executive Director at DataHaven, a formal partner of the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership with a 25-year history of public service to Greater New Haven and Connecticut. DataHaven’s mission is to improve quality of life by collecting, sharing and interpreting public data for effective decision making.