Mapping Communities at Risk: Federal Policy Changes That Could Triple Connecticut Homelessness

By Nat Markey (DataHaven), Mark Abraham (DataHaven), Jackie Gardner (ACT), and Katie Jennings (CCEH)

Introduction

Connecticut faces a growing homelessness crisis that could become far worse due to proposed policy changes at the federal level. Under a recent policy shift, more than 6,000 Connecticut residents currently housed in permanent supportive housing programs could have lost their homes, which would have tripled the state’s homeless population. This report published by DataHaven, United Way of Connecticut, the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness (CCEH), and Advancing Connecticut Together (ACT) aims to illustrate the detrimental impact of potential federal cuts, contextualize homelessness in Connecticut, and suggest realistic policy solutions.

According to annual Point-in-Time counts, homelessness in Connecticut has increased each year from 2021 through 2025. The rise in unsheltered homelessness is particularly alarming, climbing from 294 people on a given night in 2022 to 833 people on a given night in 2025—a 183 percent increase. This included a 45 percent jump between 2024 and 2025.

Federal Funding at Risk

The federal funding that Connecticut relies on to provide stable housing to thousands of residents became uncertain in the fall of 2025. On November 13, HUD issued a new funding notice, known as a Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO), that would have drastically shifted billions of dollars away from the nation’s permanent housing programs. Specifically, the NOFO sought to modify the Continuum of Care (CoC) budget, which supports permanent housing and housing-first programs. The policy shift would have slashed permanent housing funding from 87 percent of the CoC budget ($3.3B) to a maximum of 30 percent ($1.1B), putting “approximately 170,000 formerly homeless people, including families with children, people with disabilities, veterans, and older adults, at risk of returning to homelessness,” according to Renee M. Willis of the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

This change came in spite of evidence showing that permanent supportive housing is the most effective method of reducing homelessness, while transitional housing is less effective (Urban, Peng at al. 2021, Tsemberis and Eisenberg 2000, Housing Matters). In the past, HUD has prioritized permanent supportive housing due to the evidence of its effectiveness, and there has been bipartisan support for this approach. Additionally, the NOFO was issued late in the funding cycle, meaning programs faced looming gaps in funding even if their awards were approved. While new awards would not have been distributed until June 2026 or later, one third of CoC programs have awards expiring between January and June 2026 (NAEH).

Immediate legal challenges from states and advocacy groups forced HUD to postpone abrupt changes to the program. In December 2025, the U.S. District Court in Rhode Island issued an injunction ordering HUD to preserve the status quo under the preexisting fiscal year 2024-2025 CoC Notice of Funding Opportunity. As of January 8, 2026, HUD announced that, as required by the court order, it will disburse CoC funds according to the system established before the November 13 NOFO.

More recently, as a result of these advocacy efforts, Congress included provisions in the final FY 2026 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 119-75) to ensure the swift renewal of FY 2025 CoC funding and to provide certain protections with respect to the FY 2026 CoC competition. Specifically, with respect to FY 2025 CoC funding, HUD must immediately non-competitively renew all projects expiring in quarter one (January through March) of 2026 for a 12-month period. With respect to FY 2026 CoC funding, HUD must keep Tier 1 funding, which is the amount of funding that is awarded based on CoC priorities, at 60 percent of a CoC’s Annual Renewal Demand (ARD) or higher. HUD must also release the FY 2026 Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for the CoC Program by June 1, 2026, and make awards by December 1, 2026. This is intended to prevent the delays and chaos that have characterized the FY 2025 funding process.

The passage of the FY 2026 Consolidated Appropriations Act is a positive sign for Connecticut’s homelessness response system. However, it is important to point out several gaps that remain. First, CoC funding was flat between FY 2024 and FY 2025, meaning that current funding levels do not account for inflation and rising housing costs. As a result, there will likely be a gap between the amount available in FY 2026 and the amount needed to cover eligible renewals. This includes more than 200 projects awarded originally under the Special NOFO to Address Unsheltered and Rural Homelessness, which were not eligible for renewal in FY2025. Second, while HUD has historically set Tier 1 funding at 90% or more of a CoC’s ARD, the change to set it at 60% or higher could affect the amount of CoC funding Connecticut ultimately receives, resulting in cuts to critical housing resources and placing thousands of Connecticut residents at risk of homelessness. Third, lawsuits filed against HUD in the U.S. District Court of Rhode Island remain pending as of early February 2026. HUD has submitted filings as recently as February 6, 2026 in both Case 1:25-cv-00626, State of Washington v. United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Case 1:25-cv-00636, National Alliance to End Homelessness v. United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, maintaining that “[t]he passage and enactment of the most recent applicable appropriations act on February 3, 2026, affirms that Congress intended HUD to have the discretion to revise NOFOs and to renew projects competitively.”

In light of these gaps and threats, is vital that Connecticut policymakers continue to work to address community needs, remain vigilant, and be prepared to take immediate action should further funding disruptions occur.

Mapping Potential Local Impacts

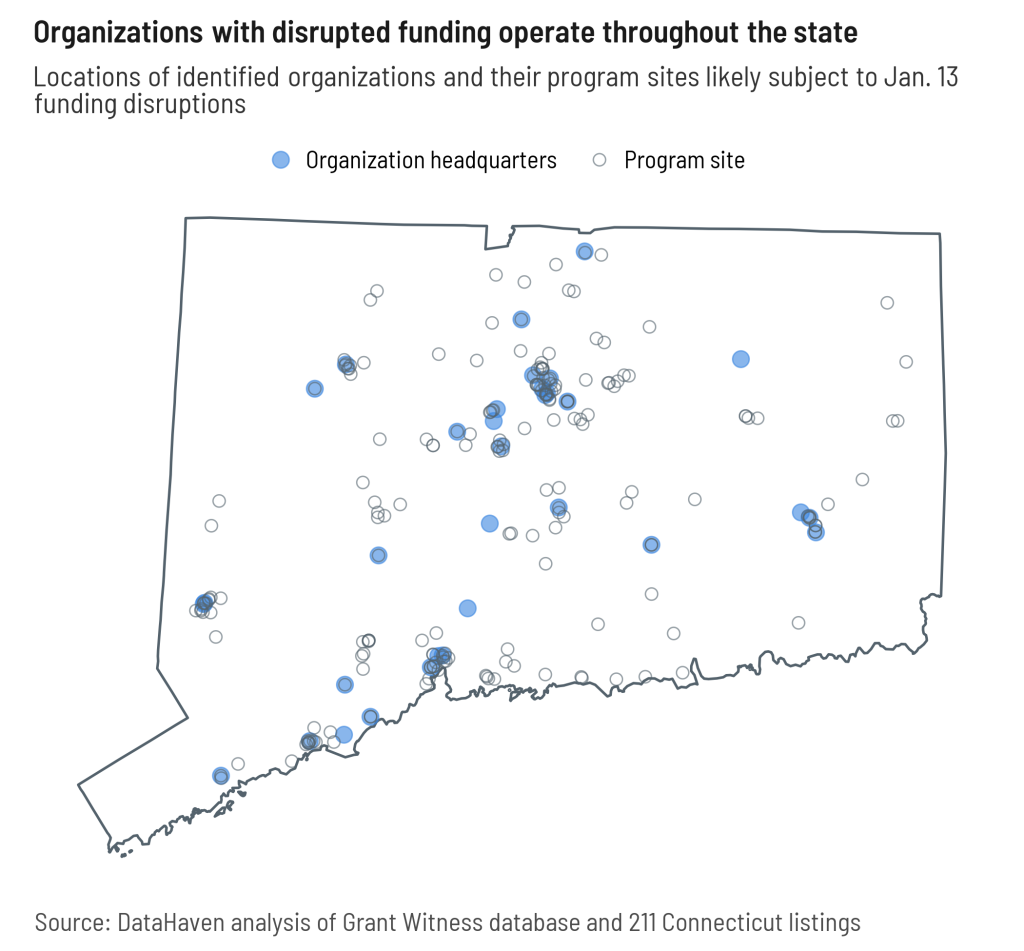

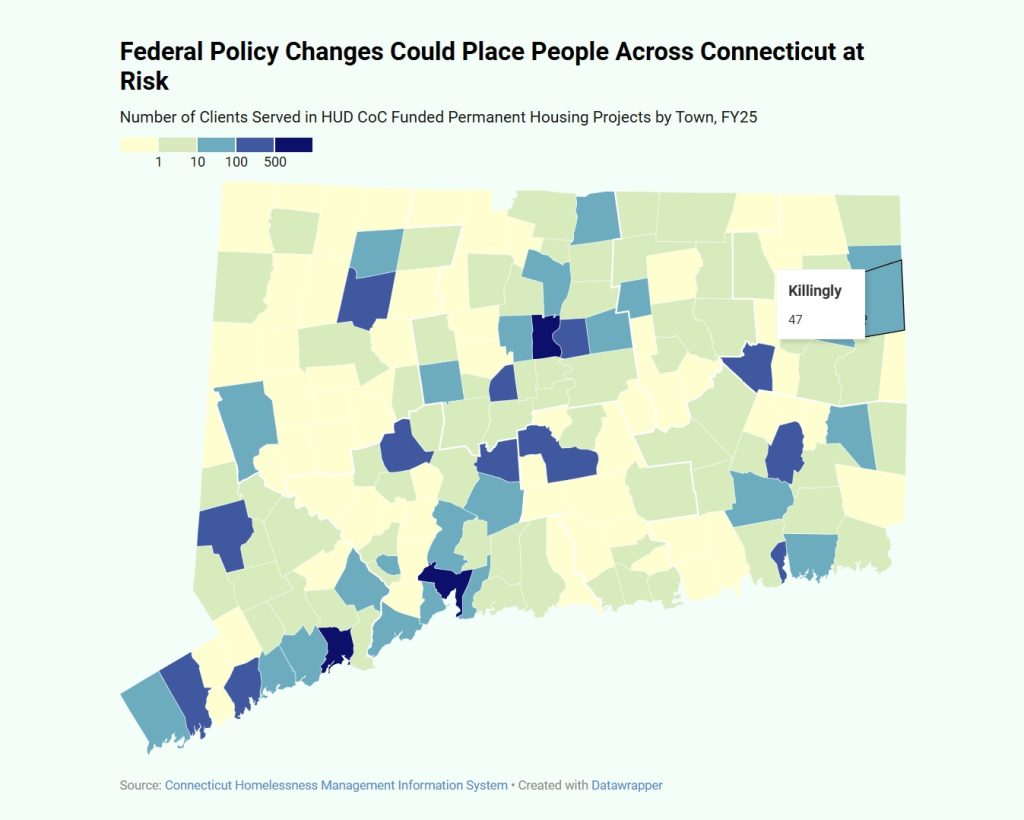

Data from the Connecticut Homelessness Management Information System show that over 6,000 people across the state are in CoC-funded permanent housing projects, meaning that they are at risk of losing their housing from any future HUD cuts. Under the recent HUD announcement, the state would have lost up to $98 million per year in federal funding for homelessness response.

Homelessness is a statewide issue in Connecticut, not just an urban one. Homelessness exists in small towns and rural communities, shoreline and tourism-based economies, and suburban communities, which often have little shelter capacity. Additionally, people sometimes must seek services outside their home town, which can mask local impact. Even examining data on where people are served, the maps below demonstrate that homelessness affects all types of Connecticut communities. For example, in State Senate District 29, which is positioned in the mostly-rural northeast corner of the state, over 200 people would be at risk of losing permanent housing in the event of these HUD policy changes. Over 100 people would be at risk in State Senate District 30, located in the far northwest corner of the state. Urban centers, which often provide services for adjacent towns, would be especially impacted. Approximately 1,000 people in New Haven, 800 in Hartford, 600 in Bridgeport, 400 in Stamford, and 300 in Waterbury would be at risk of losing their permanent housing. Smaller cities would be hit hard as well, with over 200 people at risk of losing their permanent housing in New London’s State House District 39, the most of any State House District in Connecticut.

Background: Understanding Homelessness in Connecticut

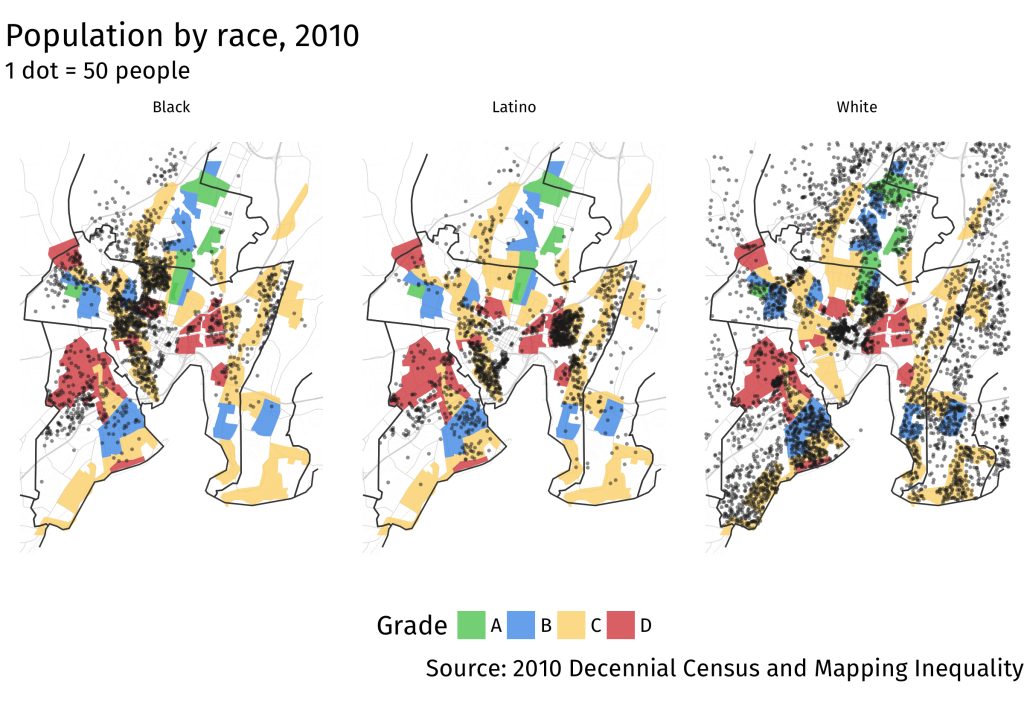

Understanding what actually causes homelessness is critical to solving it. While the current federal administration has justified its policies by arguing that substance abuse and mental illness are the “root causes” of homelessness, Connecticut data tells a different story, suggesting that income and housing affordability are the most important factors.

When people enter emergency shelters in Connecticut, they provide information about the circumstances leading to their becoming homeless. They often provide multiple factors contributing to their loss of housing, and they are asked to select one of those factors as the primary reason they became homeless. In Connecticut, the top three primary causes of homelessness—together representing 63 percent of all emergency shelter clients—were related to income and housing affordability. The most common primary cause was “expenses exceed income,” followed by “doubled up” (meaning people are sharing housing with others due to losing their own) and “legal eviction or foreclosure.” Substance use disorder and mental health problems were each the primary cause for fewer than one in ten clients (see below).

Primary Causes of Homelessness, FY2025

Expenses Exceed Income: 28%

Doubled Up: 22%

Legal Eviction or Foreclosure: 13%

Mental Health Issues: 9%

Substance Abuse Problems: 9%

Physical Health Issues: 7%

Domestic Violence Victim/Survivor: 4%

Other Reasons: 8%

Source: Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) Emergency Shelter Intake Data Collection

Rising housing insecurity and decreasing housing affordability help explain Connecticut’s recent increase in homelessness. Results from the DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey (DCWS) indicate an all-time high in housing insecurity. In 2025, 11 percent of adults in the state—over 300,000 people—said they ran out of money for housing in the past year, with this share approximately doubling since the survey was first conducted in 2015.

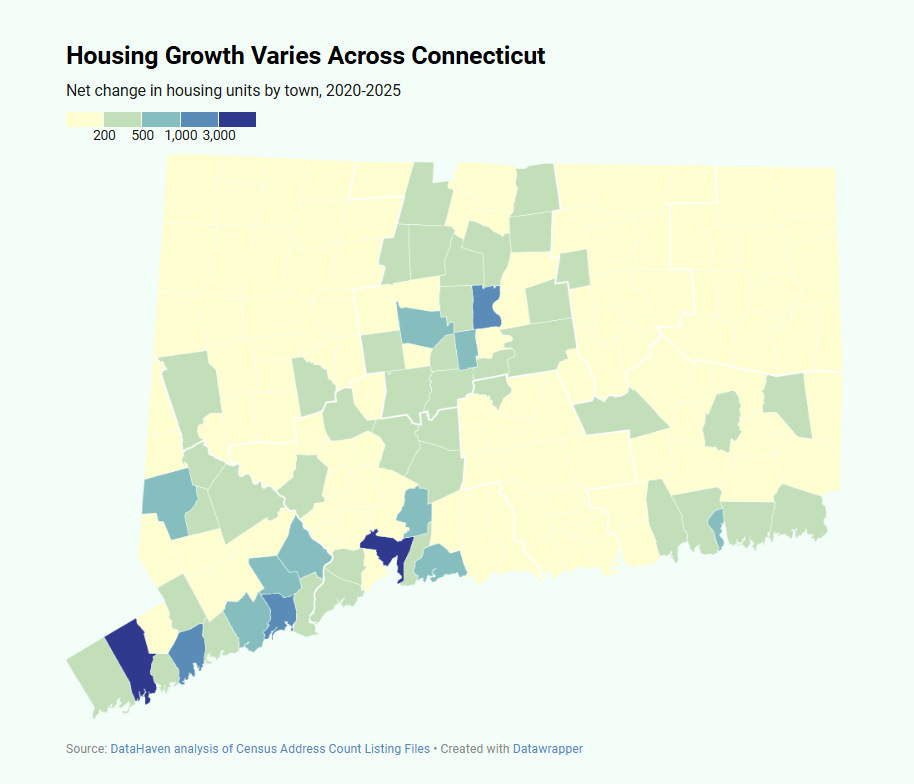

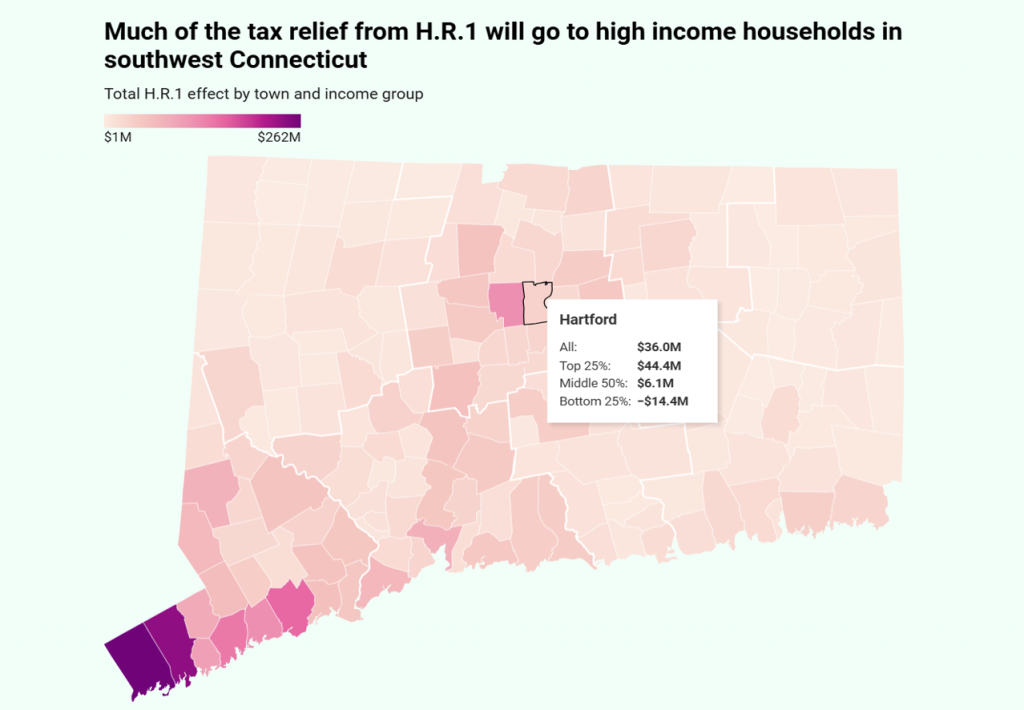

Connecticut’s housing market has become increasingly tight since the pandemic for both buyers and renters. Although a new Census data source shows that the state increased housing production and gained 40,000 new housing units from 2020 to 2025, the value of a typical home has jumped 59 percent since 2020, the third biggest increase of any state in the nation, while the stock of housing inventory actively for sale has dropped by 69 percent since 2019, the biggest decrease of any state. Meanwhile, Connecticut saw a 34 percent increase in average two-bedroom fair market rent and a 35 percent increase in average one-bedroom fair market rent from 2020 to 2025.

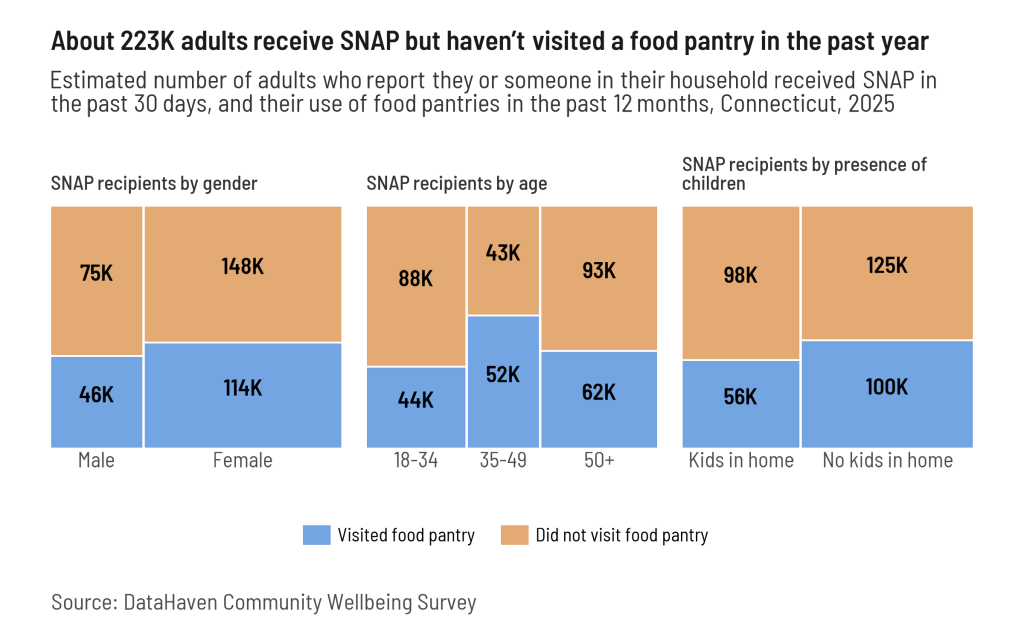

According to Advancing Connecticut Together, average rental assistance payments on behalf of clients have increased by 50 percent in recent years to keep pace with rising housing costs. Although the average amounts are still below the fair market rent benchmark, indicating that Connecticut is stretching dollars to help as many people as possible, rising costs mean that fewer people can be served with the same amount of funding. The federal government’s unprecedented cuts to SNAP, Medicaid, and other programs that benefit hundreds of thousands of low-income households in Connecticut could further compound the severity of homelessness in the state.

People of all ages and abilities in Connecticut experience homelessness. Data on people served by both emergency shelter and street outreach programs show that 23 percent of people in emergency shelters, and 27 percent of people enrolled in street outreach, are age 55 or older. Families with children are also at risk: 18 percent of people in emergency shelters are children. Additionally, 42 percent of emergency shelter clients and 57 percent of street outreach clients have one or more disabling conditions.

Affordability challenges are not going unnoticed by Connecticut residents. According to the 2025 DCWS, Connecticut residents are widely concerned about government response to these challenges. Over 60 percent of adults statewide say the government is providing too little assistance to support safe, high-quality housing for people with limited incomes, compared to only 10 percent who say that the government is providing too much assistance. An even greater majority—nearly 3 out of 4 adults—are somewhat or very concerned that current governmental policies will cause more people to have trouble affording housing.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Connecticut’s homelessness crisis demands urgent attention at the local, state, and federal levels. The data are clear: unaffordability is a primary driver of the rapid increase in homelessness in Connecticut, and the more than 6,000 residents in permanent supportive housing remain at risk from any future HUD policy shifts. The potential costs to communities and individuals are enormous.

Housing advocates are sounding the alarm about these compounding pressures. According to Lisa Tepper Bates, President and CEO of United Way of Connecticut, “the rising cost of essentials—from food to utilities to housing—has created a perfect storm for families across our state. United Way of Connecticut 211 sees the strain every day: last year, one in three calls was related to housing or homelessness—a more than 25 percent increase over the past five years. Proposed federal cuts to housing and homelessness services threaten to make this situation worse.”

According to Sarah Fox, CEO of the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness, “Recent developments have demonstrated how tenuous the availability of federal funding can be. This moment calls for a response equal to the need before us, especially as federal funding grows increasingly uncertain. If we are serious about preventing, responding to, and ultimately solving homelessness, we must scale coordinated statewide investment to the size of the problem.”

As legal challenges and policy shifts continue, Connecticut should act now to strengthen its housing programs. The state needs immediate action to stabilize housing programs that are so important across all communities, to address the affordability crisis that is driving sharp increases in homelessness, and to protect the evidence-based programs that have proven effective at keeping people housed.

Related Reports

Related Data

Document

Stamford Needs-Based Affordable Housing Assessment (PDF)

Dataset, Map

Connecticut State Legislative District Profiles

Dataset, Map

Connecticut City Neighborhood Profiles

Document

Housing Connecticut’s Future 2021 Report (PDF)

Dataset

2020 Census Redistricting Data and Change Since 2010 Census

Document