[Excerpt from 1/2/19 CT Mirror article by Jake Kara about the DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey, which is accompanied by graphs. The article also appeared on the front page of about 8 major Connecticut newspapers, including Stamford Advocate, New Haven Register, Torrington Register-Citizen, and Connecticut Post.]

Connecticut residents who said in a recent survey that they received less respect or poorer treatment than others from health care providers linked that discrimination to their health insurance status — more than race, age or gender.

Race was the most cited answer among those who felt unfairly targeted by police.

Gender and age topped the list of reasons people said they received inferior services from someone such as a plumber or a mechanic.

Among women who felt unfairly passed over for a promotion or job, 30 percent said gender was the main reason.

These experiences of discrimination — not just racial, but relating to gender, sexual identity, appearance, education — are captured in new questions on a survey that takes a broad look at quality of life in Connecticut.

The 2018 Community Wellbeing Survey is the third release of the every-three-year effort by the New Haven non-profit DataHaven to survey more than 16,000 residents, representing every town in Connecticut.

It’s a big undertaking, all done by telephone.

“In-person surveys, there’s something called the social desirability bias,” said DataHaven Executive Director Mark Abraham. “You’re more likely to give socially desirable answers. I think the telephone interview really eliminates that.”

Among people who pick up, about one in five take the survey, which lasts an average of 19 minutes. The length can vary a lot because some questions have follow-up questions depending on the response.

The project began as a way to pool resources among roughly 15 groups in the state that were conducting their own redundant — and expensive — quality-of-life surveys. It’s grown into a data product that helps non-profits, health departments and academic researchers alike better understand the population.

Questions cover a range of topics about people’s satisfaction with where they live, how safe they feel, how much they trust their neighbors and their financial and housing situations — but mental and physical health are a large part of the focus. Other new questions this year cover opioids and marijuana use.

Discrimination, perhaps more often seen through a civil rights or economic equality lens, ties into public health.

“It’s been shown to have a large impact on people’s health, so it’s sort of this form of stress in society that translates into high blood pressure and other health conditions that it’s hard to capture that as a source in other ways,” Abraham said.

There’s a growing body of research finding links between discrimination and poor health.

Questions relating to discrimination in this survey are based on existing research and borrow from a measure called the Experiences of Discrimination scale, Abraham said.

Including these questions on a regular, statewide survey doesn’t appear to be widespread in many other states around the country.

David R. Williams, a leading researcher in the field at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, developed the Experiences of Discrimination scale. He said that such data has been collected nationally for certain studies, but having the state-level data would be “very valuable.”

Experiences of discrimination in health care

Overall, 10 percent of respondents statewide said they had “ever been treated with less respect or received services that were not as good as what other people get” when seeking health care.

Poorer, younger, less educated, women, and non-white respondents were more likely to say they’d been treated this way than wealthier, older, more educated, male, and white respondents.

Overall, more people felt these experiences were related to their health insurance status (26 percent) than any other reason. The next-most common response was simply that they didn’t know why they were treated unfairly — 23 percent gave that answer. Some 17 percent said the discrimination was based on race and another 7 percent said it was due to ancestry or national origin.

Among different subgroups, the reasons people felt discriminated varied.

Just 6 percent of whites who experienced discrimination in health care felt race was the reason, compared with 48 percent of blacks and 29 percent of Hispanics.

Among women who experienced discrimination, 16 percent said it was because of gender, compared with 6 percent of men.

Transgender patients avoiding health visits

While only some questions specifically address discrimination, many of the questions give insight into disparities in the wellbeing of different demographic groups because the responses are tallied by race, gender, age, education and income.

A small number of respondents, about 100 of the more than 16,000, consider themselves transgender, and they were asked about how they experience the health care system.

Among those who identified as transgender, some 42 percent said that in the past 12 months they had avoided necessary health care visits because they were afraid of being disrespected or mistreated.

A similar 41 percent of transgender respondents said their doctors do not provide what they consider gender-inclusive care. More than half of those who responded that way told interviewers it was because their doctors do not treat transgender-specific health issues or lack knowledge of transgender-related health care issues.

When patients said they were offered inclusive care, the most common explanation, given by two-thirds of respondents, was that they believe their providers are comfortable with patients who identify as transgender.

These numbers align with a more qualitative insight contained in a report released this week by the state’s Getting to Zero Commission, an effort to eradicate new HIV cases. In that report, a common theme from listening sessions with transgender women in five Connecticut cities was the need for better understanding of transgender identity and care issues.

Other forms of discrimination

While the large majority of respondents reported not having been discriminated against in the health care system, other kinds of discrimination were more common.

More than a one-in-four, or 27 percent, said they had been unfairly passed over for a job or promotion. Of those people, 20 percent said gender was the main reason, while 17 percent attributed it to race and 15 percent said it had to do with age.

Just 4 percent of overall respondents said they had been kept out of a neighborhood because a realtor or landlord unfairly refused to sell or rent them a home. This experience was much more common among blacks (9 percent) and Hispanics (10 percent) than whites (2 percent). Among those who had this experience, 35 percent said it was due to race.

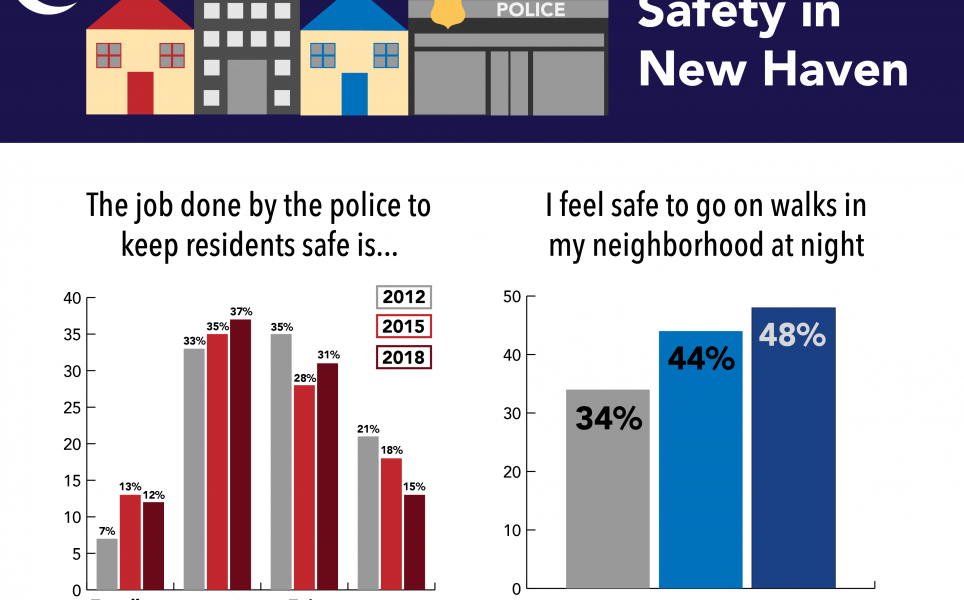

Similar disparities existed in interactions with police.

Nine percent of whites said they had been unfairly stopped, searched, questioned, physically threatened or abused by police, compared with 17 percent of Hispanics and 24 percent of blacks. While whites who reported this discrimination felt it was most often (19 percent) because of some other aspect of their physical appearance, 77 percent of blacks and 55 percent of Hispanics felt the discrimination was mainly race related.

In addition to the state-level data, DataHaven will gradually publish data at the town level starting with some of the larger municipalities.

Link:

https://ctmirror.org/2019/01/02/discrimination-questions-add-new-depth-wellbeing-survey/