All DataHaven Programs, Health, Public Safety

With over 1,000 Connecticut deaths last year, opioids demand even greater attention during pandemic

by John Park

The current opioid epidemic began 20 years ago as people’s lives were ruined by the very substance that was supposed to relieve their pain. With the rise of synthetic opioids, we have seen an alarming and continued increase in drug overdose deaths. Annual drug overdoses in Connecticut surpassed 1,000 deaths in 2019, and 94 percent of those deaths involved opioids or opiates, including heroin, fentanyl, and a variety of prescription opioids.

The story of America’s opioid epidemic is intertwined with the epidemic of mass incarceration and disinvestment in Black communities. As calls to defund police departments and invest in Black communities reach local and state governments, a long-term redistribution of some of these funds toward combating the opioid epidemic is urgently needed.

According to Connecticut’s Office of Policy and Management, in 2016, 52 percent of people who died from an overdose had been incarcerated at some point in their lives. Incarceration creates an environment of risk for opioid-related overdose—including trauma, suicidality, disruption of social relations, interruptions and barriers to medical care, and social stigma—that persists long after people are released. The current investment in the criminal justice system is worsening this crisis.

For opioid drug users, the COVID-19 pandemic adds crisis on top of crisis. Physiologically, opioid users may be more vulnerable to health complications related to COVID-19 because of compromised respiratory and pulmonary health. Socially, since opioid addiction is a disease of isolation, the social isolation under the pandemic may cause people to relapse and increases the risk of overdose. Due to stigma and profit-driven structures that have criminalized drug use, drug users are more likely to be incarcerated or homeless—both alarming risks in the face of the virus, and both situations that make good hygiene difficult and social distancing nearly impossible.

The pandemic also presents challenges for therapy clinics and harm reduction programs. Governor Lamont’s executive order to expand Medicaid during the outbreak permitted methadone clinics to continue Medicaid services via telehealth. But this shift to online health care reveals another disparity: access to broadband. Equitable access to health care will remain far from reach without addressing the digital divide in Connecticut. Increasing support to harm reduction programs, such as syringe exchange centers and naloxone providers, will also be crucial to keep the COVID-19 pandemic from undoing the state’s decade-long effort to curb the opioid epidemic. In Manchester, a recent USA Today report highlighted how therapy centers are not only losing funding due to the cutback in in-person programs, but have also been blocked from federal relief funds, resulting in life-threatening consequences for their patients.

More up-to-date data are needed to fully understand how the pandemic is affecting drug overdose rates in Connecticut. In Cook County, Illinois, opioid overdose has caused twice as many deaths so far this year than the same period last year.

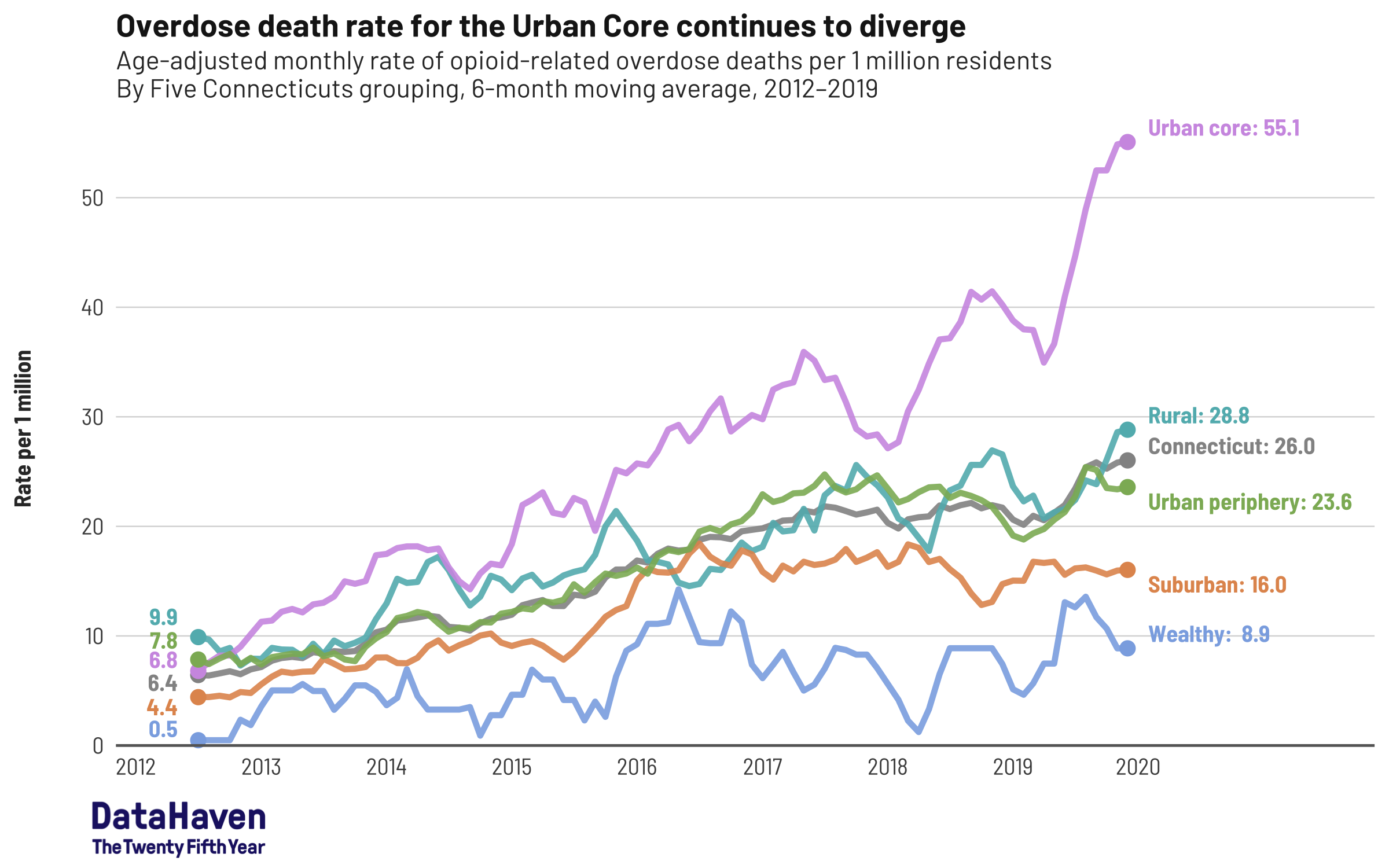

In Connecticut, the opioid epidemic has sometimes been associated more with rural communities. But since 2012, the problem has become most acute in our city centers, where COVID-19 has also hit hardest.

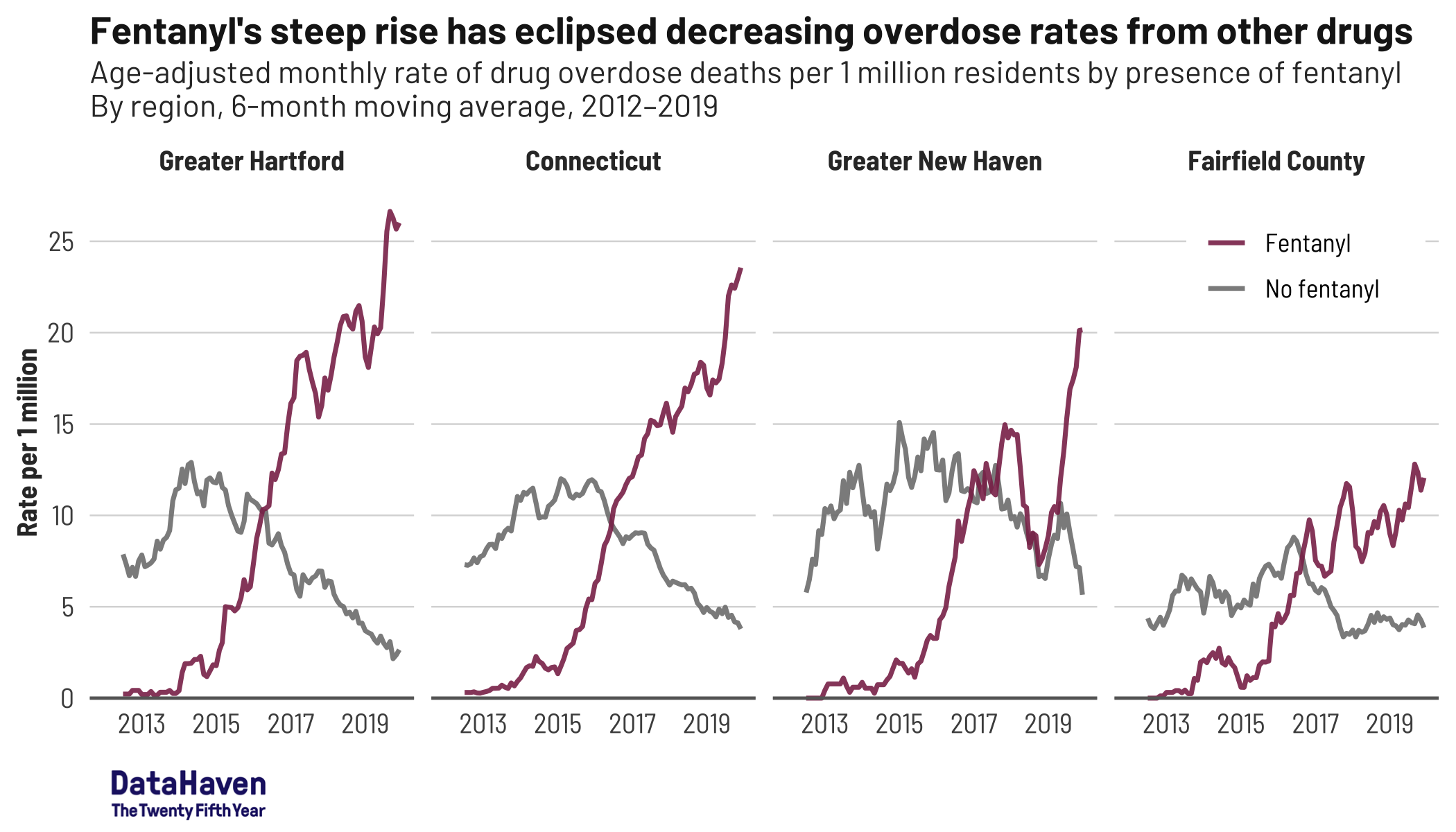

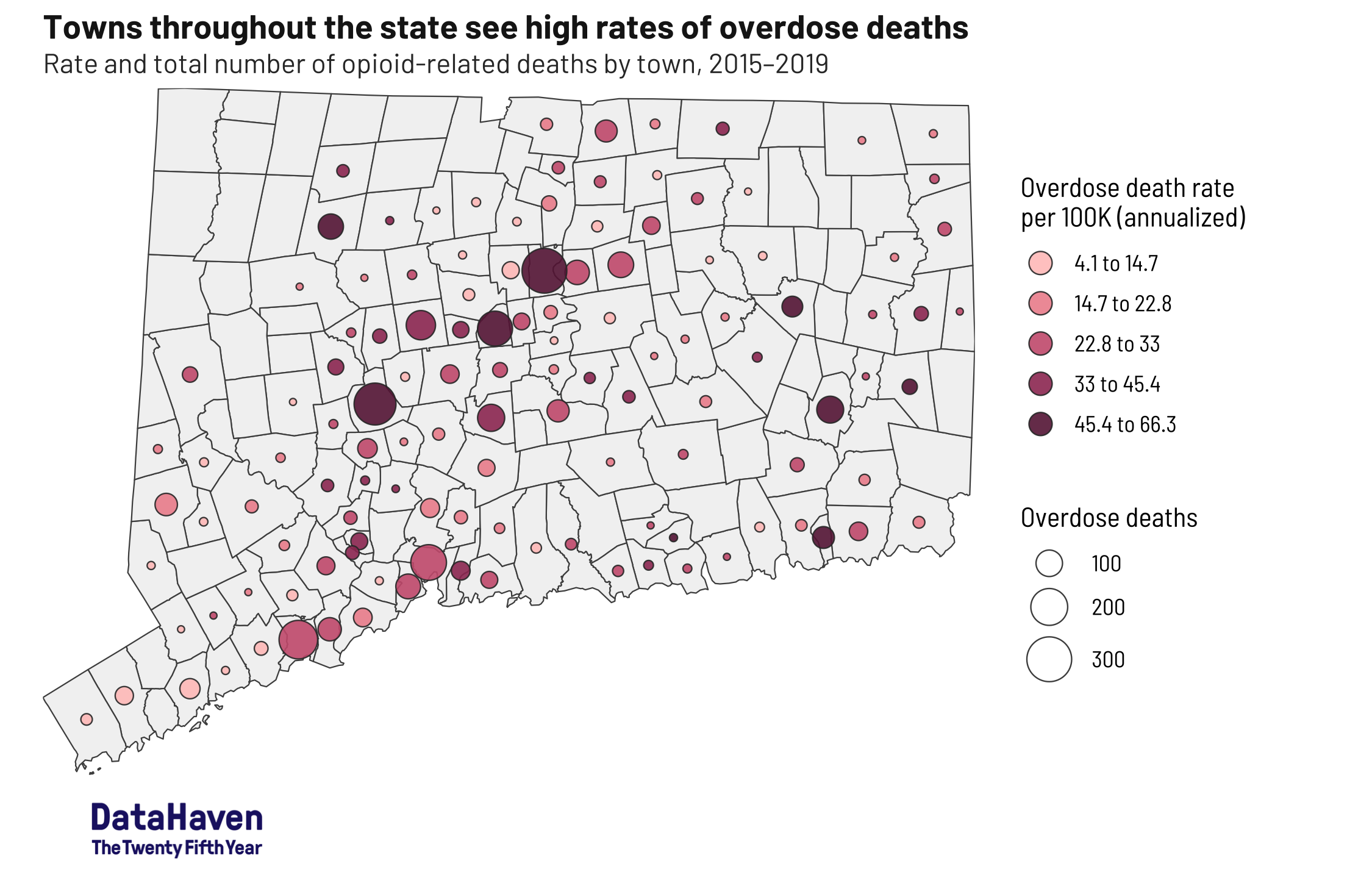

According to DataHaven’s newly released publication, “Towards Health Equity in Connecticut: The Role of Social Inequality and the Impact of COVID-19”, opioid overdose deaths in urban areas are commonly attributed to illicit drug use and the surge in the presence of fentanyl in the illegal drug supply. Yet rates are not uniform. Hartford and New Britain (45 and 52 deaths per 100,000 residents, respectively) have notably higher overdose death rates than Bridgeport or New Haven (both 28 per 100,000), while rates in Stamford (8 per 100,000) are much lower. And the report shows that overdose death rates among Black and Latino residents are now as high or higher as those experienced by white residents.

The new report also notes that the reasons why people turn to illicit drugs—specifically opiates—are often related to an accumulation of social and economic factors, including adverse childhood experiences, experiences in the criminal justice system, inadequate health care, family history, and stress. For some, seeking treatment for drug misuse is complicated by mistrust of health care providers or fear of law enforcement. Some individuals give up on seeking help.

Meanwhile, in rural areas, research suggests that years of economic decline in former industrial areas, often with long histories of alcohol and drug misuse, have left residents socially and economically isolated. Many who were dealing with workplace injuries or disability may have received prescription opioids for legitimate medical reasons, then progressed toward opioid misuse over time. Nationally, about one quarter of individuals on prescription pain opioids engage in misuse. For rural individuals, access to treatment is often complicated by their distance from providers.

The opioid epidemic is not simply the sum of individual addictions. It is an economic and social phenomenon, affecting people all over the state, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made the fight against it harder. Understanding this, and ramping up our treatment and intervention response as a result, can save lives.

John Park is Research Assistant at DataHaven, a New Haven-based non-profit organization with a 25-year history of public service to Connecticut communities. Its mission is to empower people to create thriving communities by collecting and ensuring access to data on well-being, equity, and quality of life. Some of the content for this article is drawn from DataHaven’s new publication on health equity (ctdatahaven.org/healthequity), and data graphics are contributed by Camille Seaberry, Senior Research Associate.