Note: This story appeared on the front page of the Hartford Courant on Sunday, March 27. The online version contains an interactive data visualization allowing readers to explore survey data by Connecticut town, age, gender, household income, and other factors.

[Excerpt]:

The effects of poverty are profound and far-reaching, weighing on people’s overall happiness and rendering life less satisfying for people across lines of race and geography in Connecticut, according to a sweeping survey of thousands of residents last year.

The results of the “WellBeing Survey,” administered to more than 16,000 state residents, paints a picture of Connecticut in which many have access to the trappings of the modern economy and others live in a world with far less opportunity, where the tendrils of poverty invade their neighborhoods and their outlook on the world.

Connecticut’s poor — regardless of race — believe government is less responsive to residents’ needs; that they have less access to goods and services, have less faith in police, have fewer chances to obtain suitable employment, have a lesser opinion of the condition of public parks and facilities; play less of a role in government decision making; show less tendency to remain in their communities long-term; believe that their neighborhoods are less safe; have less trust of their neighbors; lack positive role models; are more likely to be in poor health; enjoy less overall life satisfaction; experience less happiness and more anxiety; and have higher rates of obese and overweight residents, lower rates of health insurance and higher rates of smoking, according to the survey.

...

The survey “confirms the impressions we all have,” said Jim Williamson, president of the Community Foundation of Greater New Britain. “I find it fascinating, if not difficult at times. We’ve been sweating over this. It’s like peeling an onion and looking for one question that correlates with another.”

The survey — designed and administered by DataHaven, a Connecticut non-profit whose “mission is to improve quality of life by collecting, interpreting and sharing public data for effective decision-making,” and the Siena College Research Institute — has given local agencies so much data to work with that some officials said it’s hard to know where to begin.

The hope of the survey is that local agencies, from governments to non-profits, can mine the results to find more effective ways to apply resources to those groups that need them and can benefit the most, said Mark Abraham, the executive director of DataHaven.

And that means delving into issues beyond simple census-like metrics of income, age, race and education.

The 80-item survey begins with a simple question — “Are you satisfied with the city or area where you live?” — and the responses outline a recurring theme.

About 90 percent of those whose household income was above $200,000 said they were satisfied with where they live. The percentage decreases in almost a straight line through income levels, to about 73 percent of those whose income was below $15,000.

“Even if it’s confirming an assumption, there’s some value to having that confirmed with high-quality data,” said Scott Gaul, the Community Indicators Project Director at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.

“There’s an expectation that this is going to be some study that comes out with a big answer, but a better way to think of it is that we’re not going to have a punchy conclusion, but it will be a resource,” Gaul said. “What’s useful about it is in the specific areas where we lack information, it’ll fill in those gaps.”

The question “overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?” returned some of the most telling responses: 90 percent of those with incomes over $200,000 said they were “completely” or “mostly satisfied.” As income fell, dissatisfaction rose. Of those with incomes between $15,000 and $30,000, only 56 percent were “completely” or “mostly satisfied”; at incomes below that, only 44 percent responded the same way.

Race and education showed similar trends: white and college-educated people reported more satisfaction with their communities and their lives.

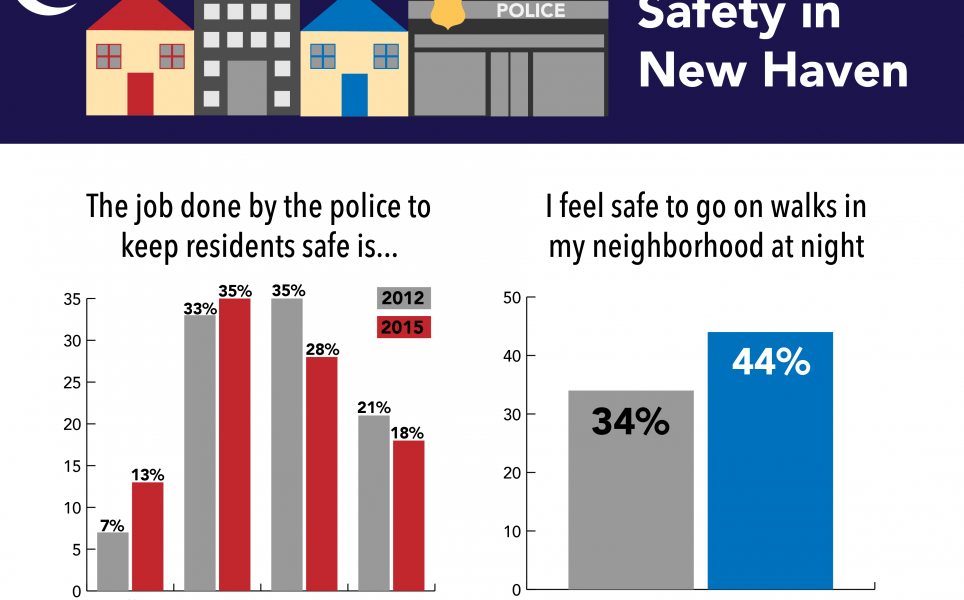

In the areas of safety and crime, the survey data shows how different Connecticut’s communities can be.

“The incidents and the nature of crime in different areas — there’s a ton of detail, but we don’t have information [before the survey] about how people feel safe in their neighborhoods. [This survey] looks at attitudes rather than administrative records,” Gaul said.

And because the survey delves more deeply into respondents’ lives, the results give a richer definition of what it means to be “healthy,” said Kristin duBay Horton, director of health in the city of Bridgeport.

“How healthy I am has a lot of factors,” she said. “Like how often I go to the doctor, the food I eat, the amount of stress in my life, whether I got a good education that gets me access to a job and health benefits and the ability to breast-feed my children. All of that plays into that actuarial table that shows how long I’m going to live. Health is about that whole wealth of things.”

But duBay Horton sees some positive signs in the data for the city of Bridgeport.

“I’m not surprised that being truly poor is hard, I’m surprised at how resilient people in the under-$30,000 [income bracket] are,” she said. “They have an ability to make the best of what has been dealt to them. [Questions about] whether or not your fire station would be closed, would people in the neighborhood organize to help do something, and whether or not they have time to do things that they truly enjoy — those show a level of resilience.”

The survey results are especially valuable for agencies at the local level, because they highlight needs in specific neighborhoods, community leaders said. Data aren’t yet available for all towns in the state, but a preliminary look at data from the biggest cities was illuminating, Abraham said.

“We’re looking within the cities to see how issues differ by neighborhood,” Abraham said. “There are vast differences. In New Haven, there’s a corridor of lower-income sections where unemployment was 22 percent. The rest of the city had 5 percent, overall 11 percent. That sounds not great, but once you break it down [into neighborhood-level data], it was a huge range.”

“That’s important to targeting programs. So if there’s a work placement program, they need to go to the neighborhoods with higher unemployment,” he said.

“We were surprised to see in towns like Berlin a fair percentage of people who feel they haven’t recovered from the recession,” said Williamson, of the Community Foundation of Greater New Britain. “We have replaced the positions that were lost, but what did we replace them with? Low-skill, low-pay jobs, and we lost living-wage jobs, in Berlin, Plainville, and New Britain. Less so in Southington.”

In New Britain, 26 percent of the nonwhite population who responded to the survey said they do not have a checking or savings account.

“How do you take out a loan or gain credit if you don’t have a banking relationship?” Williamson said.

The survey results, he hopes, can be useful for local leaders.

“We want to make sure our town governments get a copy of it — we want to be able to point out things we’re discovering, priming the pump for them,” Williamson said.

Some cities had results that differed from the state-wide numbers.

In Bridgeport, for example, the poorest residents were more likely to “strongly agree” with the statement “children and youth in my town generally have the positive role models they need around here” than middle- or high-income respondents.

DuBay Horton said a woman who works as a cashier at Shop Rite explained that best:

“Once you have more money, you’re pickier about the people your kids are hanging out with,” she said. “Once you’ve made it, what you want for your children is going to be different. If you’re struggling every day, you feel like having your kids surrounded by kids who are struggling, that’s OK because that’s how the world works. If you’re in that upper category, you want your kids to do better than you.”

The survey results will make it easier for her to get the Bridgeport city council more fully engaged in neighborhood issues, she said.

“We can talk about getting community gardens in neighborhoods, look at how the gardens may be one answer to how people are feeling cut off from their neighbors,” she said. “It is so powerful a tool because it covers such a wide range of topics.”

The survey can provide “some serious reconsideration, as a state, about social justice as a framework or a lens to look at all the work we do,” she said.

“We just keep putting Band-Aids on [social problems] instead of cutting down the pricker bushes,” she said. “And when the money gets tight, they say you’re not getting any Band-Aids. But if we could find a way to give people living wage jobs, then we wouldn’t need the expensive Band-Aids at the back end.”