by Numi Katz

On June 29, amidst pandemic-induced unemployment and economic uncertainty, the Gov. Ned Lamont’s administration released a sweeping $33 million assistance program for renters, homeowners, and local landlords. Connecticut has been lauded as a national leader in the housing policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The relief package features state and federal support, ranging from rental assistance for those experiencing income or job loss to mortgage relief programs for homeowners. Critically, the program works to augment patchwork policy at the federal level, providing support to those who may not qualify for CARES Act benefits.

With data from the Census Bureau’s new Household Pulse Survey showing that 34 percent of Connecticut renters reported having “no” or “slight” confidence in their ability to pay next month’s rent, these programs will help vulnerable individuals avert crisis.

The stress of housing insecurity and homelessness has been shown to produce marked negative effects on mental and physical health. DataHaven’s 2018 Community Wellbeing Survey found that only 34 percent of recently evicted adults reported being in very good health.

The stories behind these numbers reveal the web of factors that expose some groups to the worst effects of one health or economic crisis after another. In the four-part video series “COVID-19 Reckonings” produced by Purple States and DataHaven, we hear from community members with the most at stake in Connecticut’s short- and long-term response to COVID-19. The first episode, “More exposure,” explored the uneven spread of the virus. In the second episode of the video series, we meet Wanda, who was homeless for 32 years. In 2007, she managed to escape a cycle of abuse and addiction. But she was unable to escape the cumulative impact of so many years of homelessness on her heart. The episode, entitled “Deadlier,” conveys the danger posed by the pandemic to individuals like Wanda who are already facing adverse health outcomes.

Safe and stable housing must be seen as imperatives of the state-level reopening and recovery strategy. However, achieving an equitable recovery demands not only short-term support and relief programs for individuals but also a reevaluation of the housing policies that have made Connecticut one of the most segregated states in the country. In a state where children born in wealthy towns have a life expectancy six years longer than those born in urban areas, our pandemic response must address the network of social factors— housing, access to health care, nutrition, and economic stability— that reproduce and exacerbate unequal outcomes.

Connecticut has an unprecedented opportunity to pursue bold innovation and experimentation in housing policy: tackling long standing issues such as housing affordability, housing insecurity, and economic segregation. The far-reaching scope of the crisis unites a new coalition of renters, landlords, and homeowners in desperate need of state support that will outlast the immediate relief package. State and local policymakers must capitalize on this newfound appetite for housing reform, coordinating short- and long-term policy responses at a state and regional level. The $10 million of CARES Act funding earmarked for cities also allows them to pursue previously cost-prohibitive local housing initiatives.

Findings from DataHaven’s new report “Towards Health Equity in Connecticut” show the central role stable housing will play in achieving the goals of a successful reopening. If we hope to reunite people with jobs, we must combat evictions and the subsequent prolonged search for housing which mean that evicted adults and those who are made homeless are much more likely to experience unemployment than those with stable housing. If we hope to return children to productive learning environments, we must combat evictions, which have been shown to worsen educational outcomes for children, a trend compounded by access to many school’s education programs predicated on a child’s reliable access to the internet.

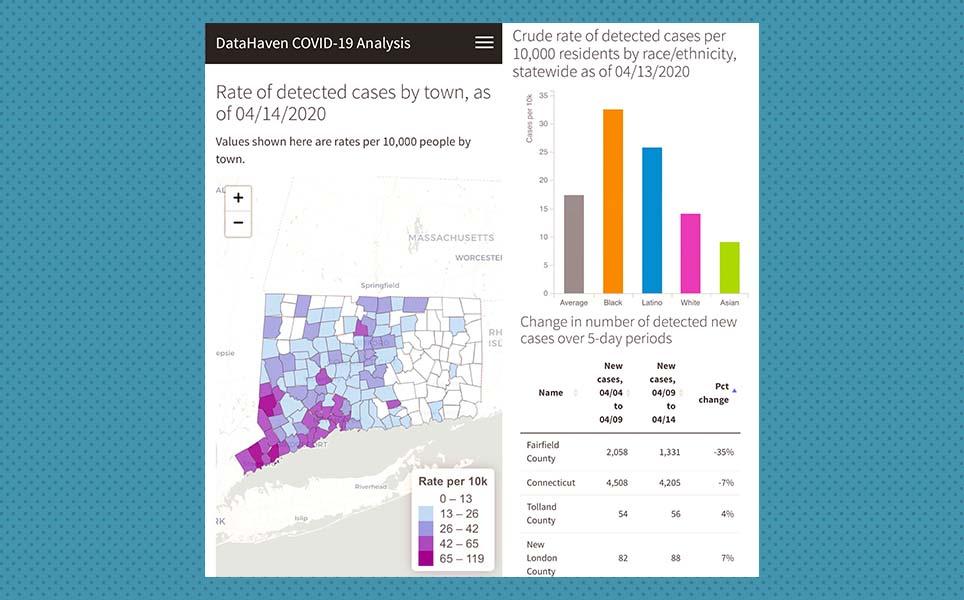

But we also know that economic hardship is not distributed equally: COVID-19 has strikingly illuminated and compounded existing inequalities in Connecticut. Policy decisions made in a more explicitly racist past have created deep and abiding inequality. We cannot excise current policy decisions from this history; rather, we must learn from the contours of inequality COVID-19 has heartbreakingly put into focus and address them head on.

Connecticut’s struggle with housing affordability sheds light on the necessity of approaching housing relief holistically. Renters, who, like Wanda, are more likely to be Black, Latino, or female, are also more likely than homeowners to experience severe housing cost burden or pay more than half of their income on housing. No part of the state is spared; for example, DataHaven’s new report finds that in Stamford and Greenwich, 36 percent of Latino, 33 percent of Black, 19 percent of Asian, and 17 percent of white households are severely cost-burdened.

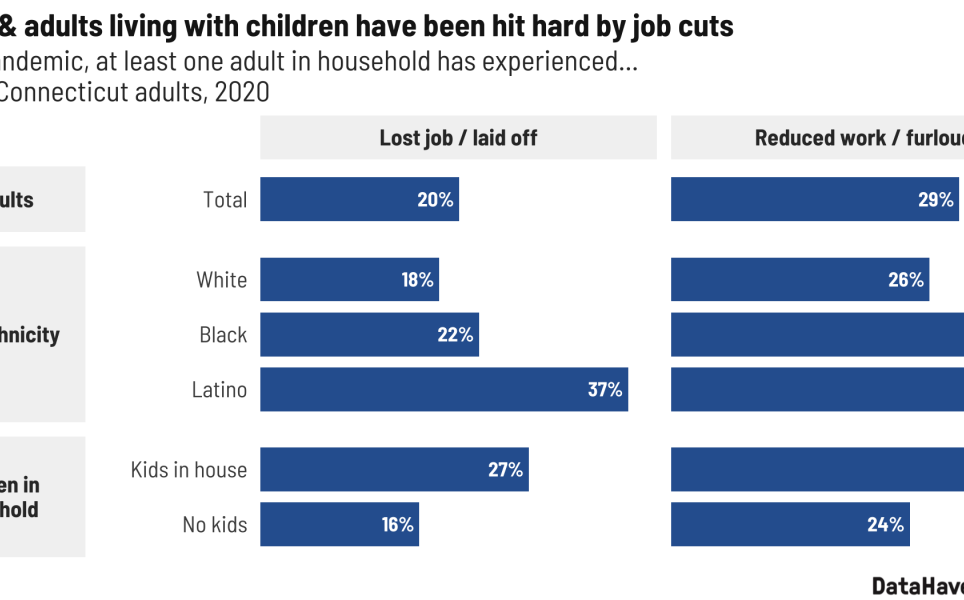

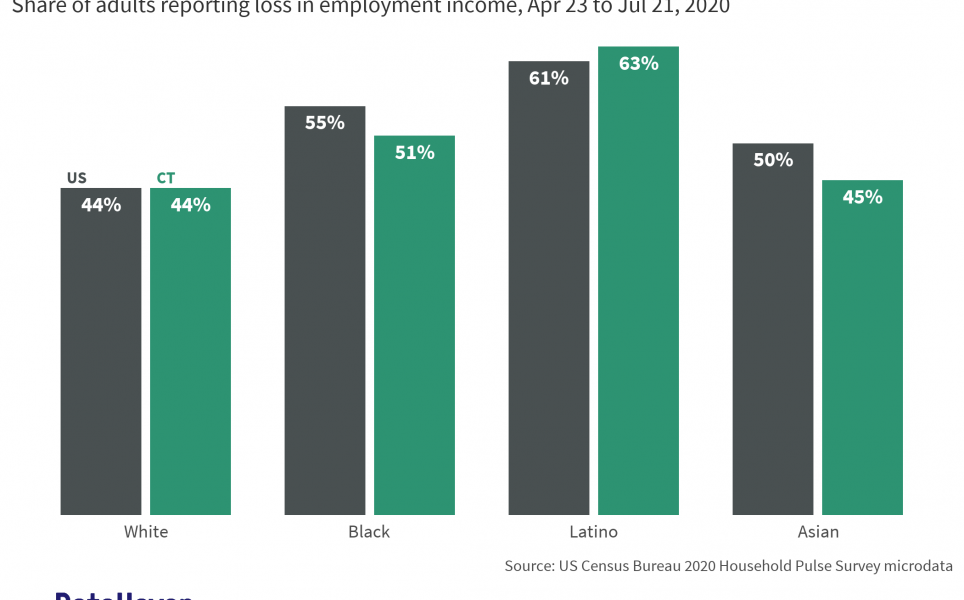

Income loss due to the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates pre-existing inequalities: data from April and May show that 67 percent of Latino households and around 50 percent of Black and Asian households reported a loss of income from employment, compared to 43 percent of white households. DataHaven analysis of microdata from the Household Pulse Survey show that 47 percent of Latino and 33 percent of Black renters reported that they were not likely to be able to make their June rent payments, compared to 19 percent of white renters.

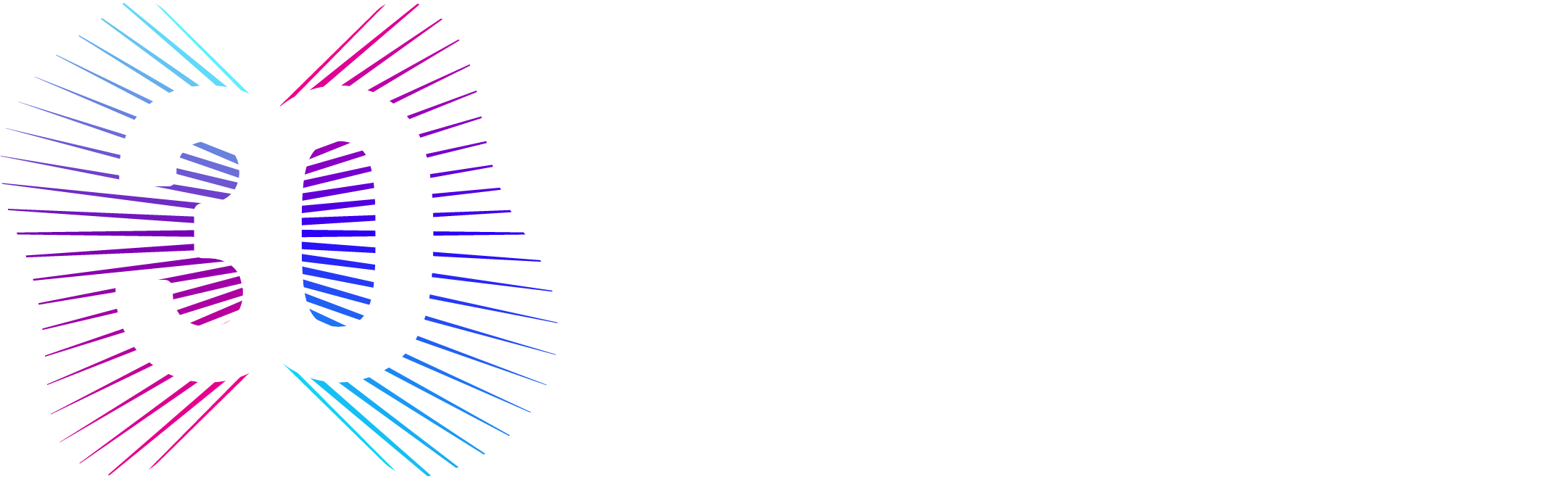

Prior to the pandemic we already witnessed Connecticut’s lopsided housing stock — with single-family homes located in predominantly wealthier suburban areas and rental as well as affordable housing located in urban areas— contributing to worsening economic and racial segregation within the state. Now, analysis from DataHaven’s COVID-19 dashboard shows that transmission of the virus has been higher in urban areas, where the pandemic compounds issues of housing insecurity, forcing residents into unsafe or overcrowded housing or for the most vulnerable, leaving them homeless.

Through policy experimentation, leaning on local data, engaging diverse and newly united stakeholders, and paying attention to the experiences of residents like Wanda and others featured in COVID-19 Reckonings, we can build more resilient communities. For example, using the new initiatives the governor’s relief program outlines for supporting homeless populations or renters as a bridge to building the long-term institutional capacity and support to improve our communities.

Through proper coordination and implementation, these programs can provide invaluable policy insight into what programs work best for our communities. We have the rare opportunity to observe how innovative housing policy — from rethinking a hyper-local approach to affordable housing to block grants for improving communal well-being— can transform communities. This information will arm us with the tools to take on the difficult task of breaking down entrenched inequalities at a state level.

The honor of being celebrated as a leader in COVID-19 housing policy comes with responsibility. We know that building communal resilience —providing people the tools necessary to emerge from the pandemic— begins at home.

Local and state officials have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to tackle not merely the consequences but the causes of inequality. By equalizing the odds of achieving health and well-being, we can emerge from the pandemic as a stronger Connecticut for all residents regardless of their zip code.

Numi Katz is at DataHaven, a New Haven-based non-profit organization with a 25-year history of public service to Connecticut communities. Its mission is to empower people to create thriving communities by collecting and ensuring access to data on well-being, equity, and quality of life. Graphics in this piece are from a new report by DataHaven.