All DataHaven Programs, Civic Vitality, Community Wellbeing Survey, Demographics, Economy, Education, Health, Housing, Public Safety

New data and resident stories inform Connecticut’s road map for recovery

[Note: This piece, by DataHaven’s Mark Abraham and Aparna Nathan, initially appeared in the Connecticut Mirror.]

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected Connecticut’s communities in ways that are deeply inequitable and detrimental to the well-being and economy of our state—as new data each day remind us.

State statistics show that Black residents have died from COVID-19 at a rate 2.7 times higher, and Latino residents at a rate 1.6 times higher, than that of white residents, after adjusting for age differences.

Since March, the novel coronavirus has spread in uneven ways. While the virus initially appeared most often in the state’s wealthier areas, our analysis shows that it quickly became much more concentrated in Connecticut’s largest cities and in 31 other towns with moderate income levels, such as Ansonia, Danbury, Manchester, and West Haven.

These places, home to just over half of the state’s population, comprise more than two-thirds of reported cases and nearly 75 percent of deaths. And although the numbers of new COVID-19 cases have fallen across the state, residents of moderate-income towns are still more likely to test positive for the virus than people in wealthier suburbs —suggesting that public health systems still have room for improvement in areas such as testing access.

A new DataHaven publication, “Towards Health Equity in Connecticut: The Role of Social Inequality and the Impact of COVID-19,” dissects the social factors that have led to such disproportionate health outcomes in the Nutmeg State, which existed long before the pandemic. Our study finds that the COVID-19 outbreak widened those gaps, and suggests a roadmap for helping close them. Looming threats such as mass evictions and a possible second wave of the virus, as well as large-scale demonstrations over systemic racism in policing and other social institutions, suggest that our leaders have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address not just the immediate health crisis, but the underlying social inequalities that complicate it.

To explore the personal significance of these findings, Purple States and DataHaven are producing a four-part video series with residents of some of the communities at greatest risk in this social, economic, and health crisis. They tell the story of the COVID-19 pandemic as it has played out in their own lives. The first episode is featured here, and illuminates the uneven spread of the virus.

Health disparities are deeply rooted in systemic social inequalities and racism. In a low-income household, when someone gets sick, medical care requires time and money the household cannot afford, leading to a cascade of economic problems. And an impoverished household is vulnerable to illness in the first place because many of the factors that promote health —food, exercise, safe housing— are expensive. It’s no surprise, then, that poverty leads to large gaps in health outcomes.

The Kaiser Family Foundation reported that, if infected, adults in households making less than $15,000 per year are over twice as likely to develop serious cases of COVID-19 compared to adults in households making over $50,000 per year.

According to our 2018 survey of adults across Connecticut, one-third of low-income adults were unable to afford food at least once in the past year, leaving them dependent on cheaper, less-nutritious foods that make developing obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic diseases more likely. Sixteen percent of low-income adults could not pay for housing at least once in the past year, and many—especially renters, who tend to be lower-income or people of color— lived in overcrowded homes, or homes with safety issues like lead paint or pests. Eviction rates were high in many neighborhoods. With their link to mental health, these issues also have an outsized impact on overall levels of well-being in our state.

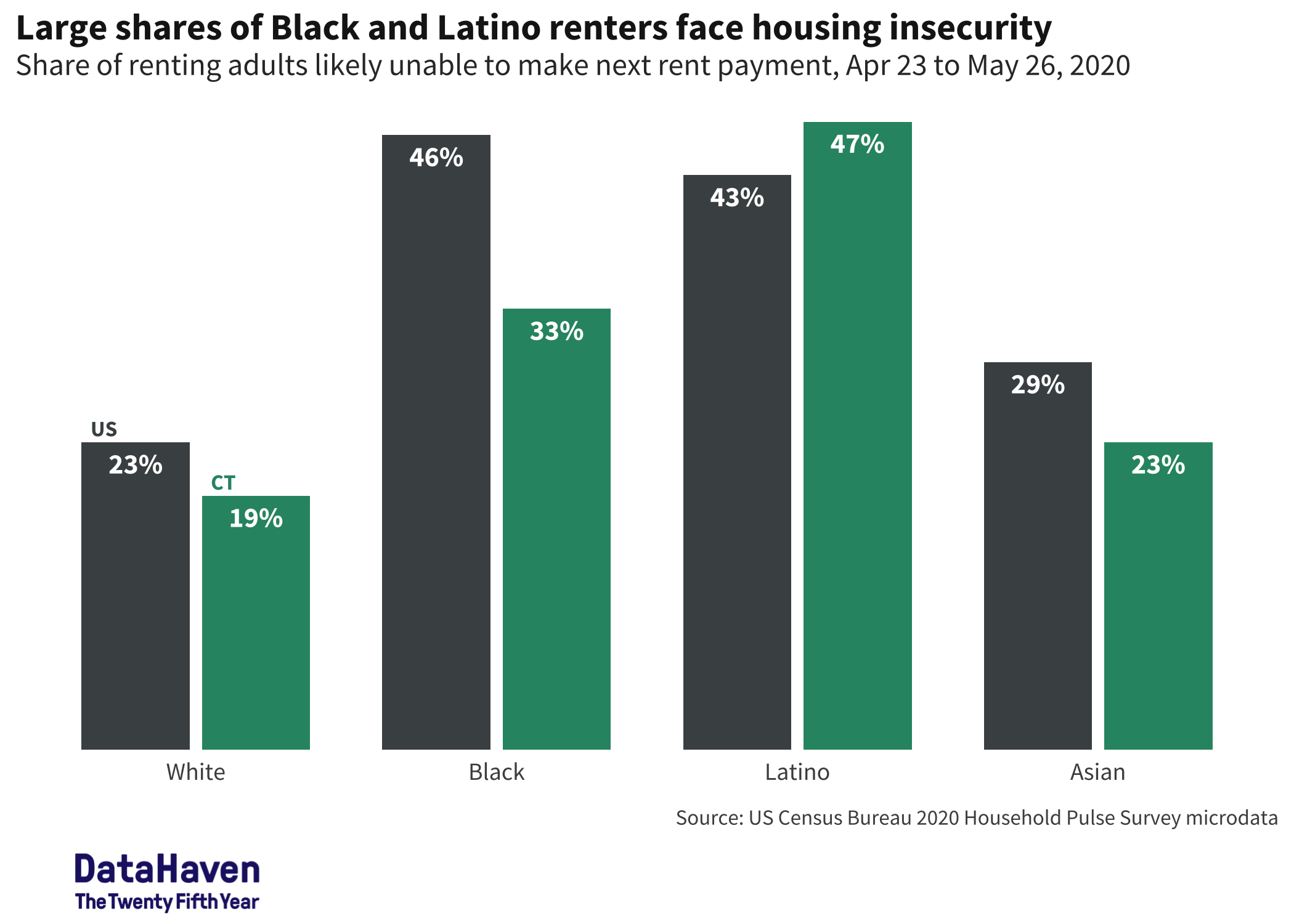

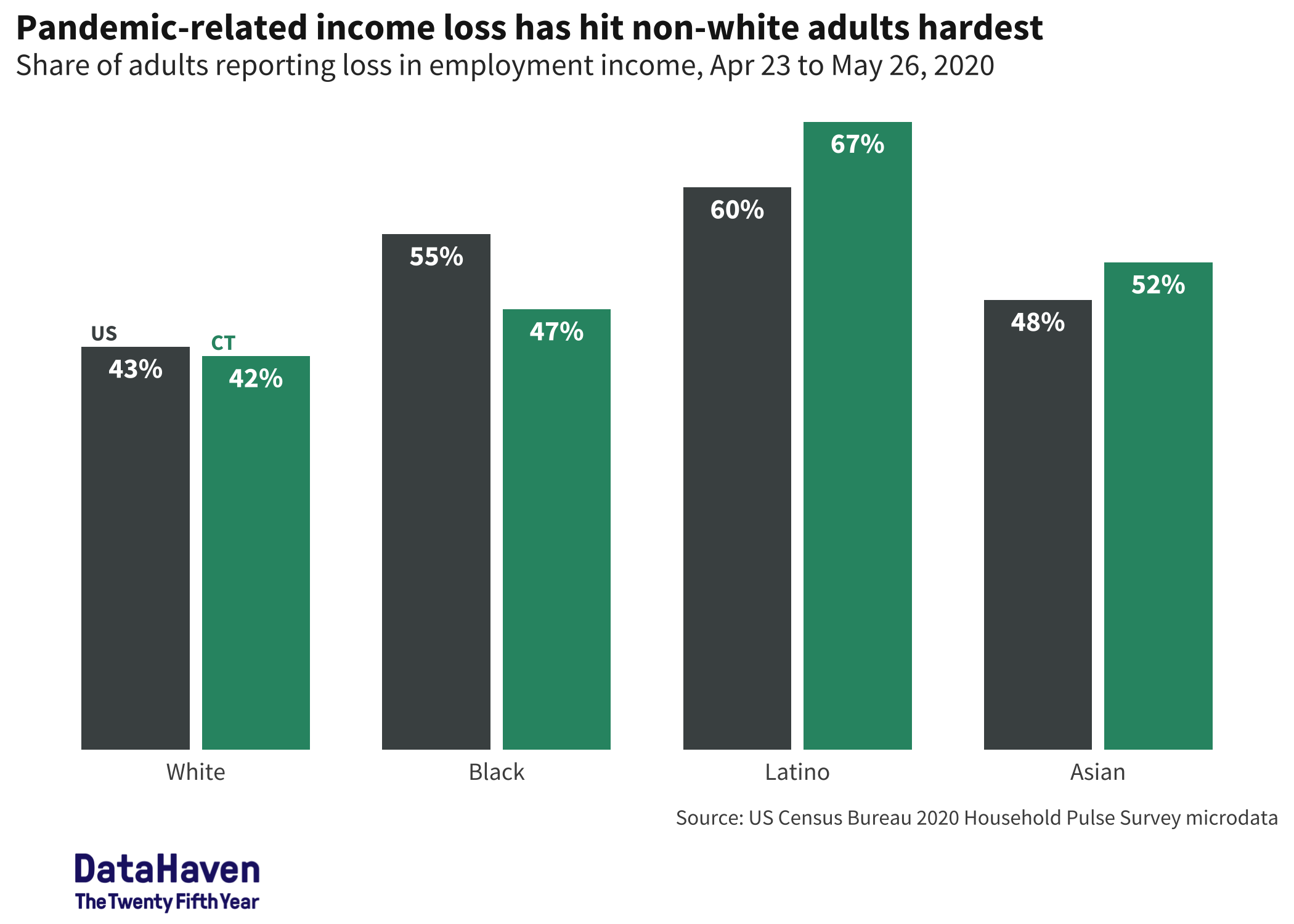

Our new report finds that the COVID-19 outbreak has amplified these problems. The pandemic has hit certain industries especially hard —such as retail, food service, and personal care— that typically employ people without a college degree, immigrants, and people of color. Sixty-seven percent of Latino adults and about half of Black and Asian adults in Connecticut have experienced a loss of employment income since March. Forty-seven percent of Latino, 33 percent of Black, and 19 percent of white renters in Connecticut reported that they were not likely to be able to make their June rent payments.

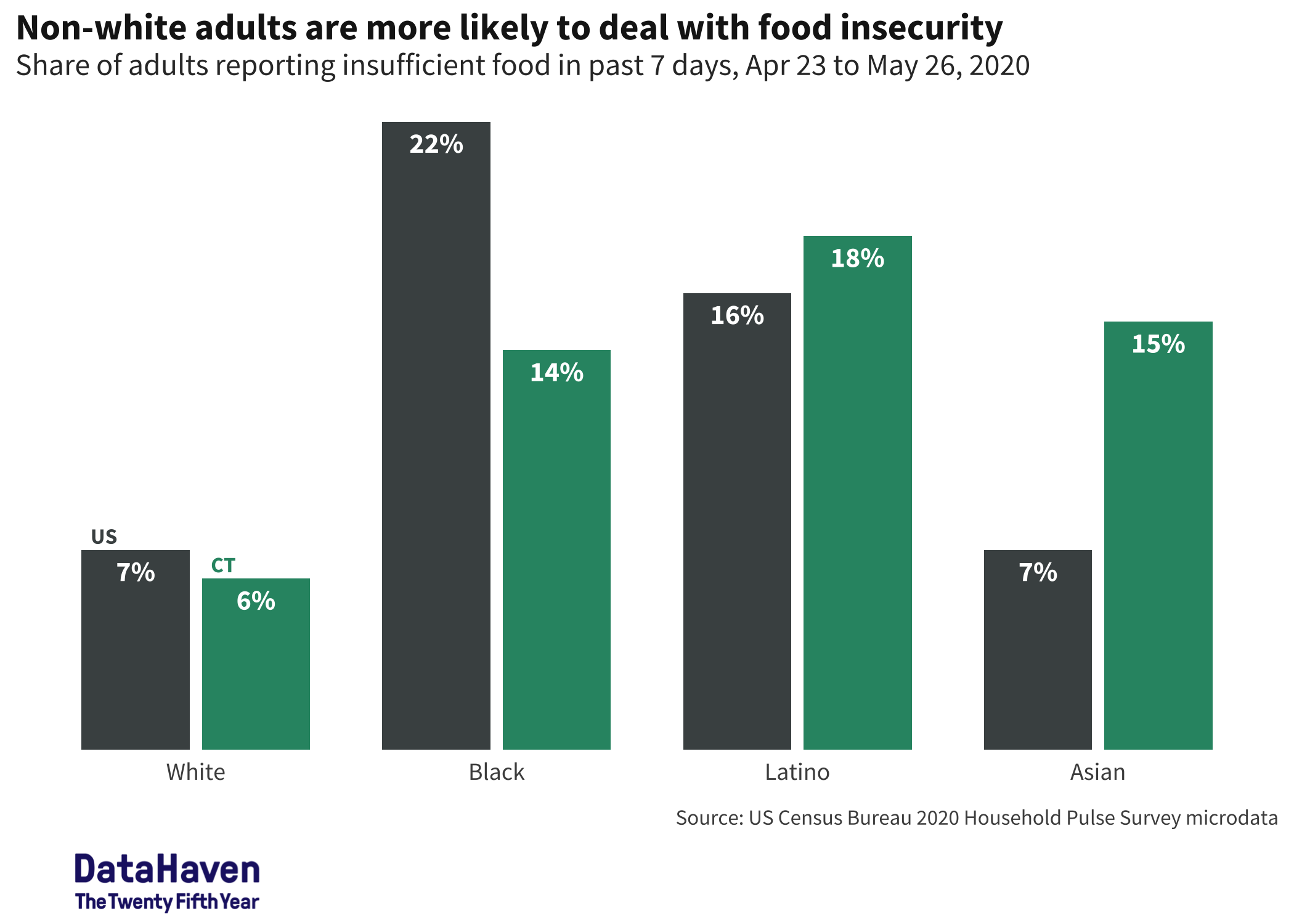

Food insecurity is at historic highs. Such inequalities place people at higher risk of COVID-19. Overcrowded homes seem to promote spread of the virus, and chronic diseases seem to lead to worse infection outcomes.

Yet the U.S. Department of Agriculture has tried to cut back already-insufficient Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. This could leave tens of thousands of people in Connecticut unable to afford food at a time when household resources are already in jeopardy. Leaders should expand SNAP benefits and other economic relief for low-income households. Similarly, a temporary moratorium on evictions and foreclosures has relieved some of the burden of housing costs, but leaves renters and homeowners unsure what will happen when the moratorium lifts before their incomes recover.

And poverty doesn’t act alone; it intersects with other structural inequalities like racism. Connecticut is a predominantly white state, but our new report’s local data appendix shows that its Black and Latino populations face higher rates of unemployment, poverty, chronic disease, food and housing insecurity across every city, suburb, and small town. Even beyond socioeconomic inequality, racism is inherently a threat to public health: A recent study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that, even after accounting for income, insurance status, and co-morbidities, counties with higher proportions of Black residents had higher COVID-19 death rates.

Our new report discusses how these gaps may be explained by stress and systemic discrimination. Decades of racist policies and practices that affect wealth accumulation and community safety, such as redlining and school segregation, have hurt Black people’s mental health. Racism is also a barrier to maintaining physical health— Ahmaud Arbery was fatally shot while going for a run— and discrimination extends into health care settings. In our 2018 survey, Connecticut residents reported discrimination in health care access on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, and insurance status. This could make people less likely to seek out care when they need it—perhaps even when they are struggling with COVID-19—and less likely to receive competent care when they do seek it out.

The need for new health care policies are critical. Non-citizens must be ensured access to medical care. Investment must rise in community health workers who can help ensure patients can get not only competent medical care, but the additional services that are essential to maintain health.

Health is a product of society, and the 20-year gaps in life expectancy in our state from one neighborhood to the next —just a few miles apart— show that our society does not give everyone an equal opportunity to achieve their full potential. Change will require collaboration between federal and state policymakers and grassroots organizations, and a substantial expansion of social services.

When we eventually emerge from the pandemic, many of us will be looking forward to a return to normal. But the old normal did not serve everyone equally. We have a chance to fix that.

Aparna Nathan is Research Assistant and Mark Abraham is Executive Director of DataHaven, a New Haven-based non-profit organization with a 25-year history of public service to Connecticut communities. Its mission is to empower people to create thriving communities by collecting and ensuring access to data on well-being, equity, and quality of life.